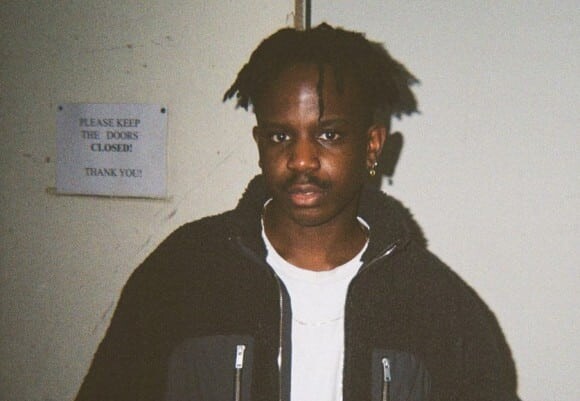

salute is blowing up. BBC and Boiler Room are pushing him, and the iconic Mixmag named him one of 22 DJs who defined 2022. Stefan Niederwieser talks to the Vienna-born, UK-based artist about depression, civil courage and finding his voice.

How proud are you of your new triple EP on [PIAS], Condition?

salute: That’s the first project where I really let UK dance music come through, and I was a little afraid about how it would be received. But so many people talk to me about it, and a lot of my best songs are on it, I’m definitely proud. “All About You” is one of my favorite songs. I love “Lafiya” too; it’s a 2-step with no shuffle, with dancehall influences – it reminds me of an era ten years ago. That track is an instrumental, not too many people know it.

Are vocals necessary?

salute: Definitely. Or if not, the synths have to be popping. For me, the vocals are often the difference between something that’s just cool and something that really slaps.

How does a musician find their sound?

salute: By making a lot of music. I’ve been making music for 14 years, and I didn’t always have my sound. I don’t listen to a lot of electronic music. The thing that makes my sound unique is all the other influences – city pop, 80s soul, and gospel. The thing I like about city pop, for instance, is that it’s so colorful and sentimental.

Are the British more competent [than Austrians] when it comes to electronic music?

salute: They’re proud of garage, grime, bassline, and drum’n’bass – all those genres were invented in England, by Black people who brought their culture with them from Jamaica and the Caribbean. With Black Lives Matter, a lot of people have become aware of this history and noticed that the music used to be political. So yes, I think there’s a greater level of competence. The country is a melting pot, there’s this hunger because poverty is a real problem. That’s not so much the case in Vienna. Affine Records was way ahead of their time, though; I still listen to them today. Props to the label, that was crazy.

“Racism is the reason I moved away.”

What are the differences in racism between here and there?

salute: In Vienna, people like to pretend it’s not all that bad, that people with dark skin are just too sensitive. But I heard the n-word fairly regularly. Racism is the reason I moved away. That would never happen in Great Britain; there’s a lot more civil courage, and people confront it. Racism there is almost accidental – like when people think I should make a particular kind of music because that’s what they think Black music sounds like.

So was your big concert at Popfest Wien satisfying?

salute: I mean…in 2017, I was standing with Valerio (MOTSA) by the backstage area smoking a cigarette, and two police officers looked over at us and whispered something to one another. I didn’t think anything of it, but Valerio’s got eagle eyes – the cops looked at me and put their hands on their weapons at the same time. And Valerio says, you see what happens here? And I’m like, yeah. They wanted to intimidate me, just these kind of psycho games. Valerio stood next to me and squared his shoulders and chest, and we just stood there for a minute and stared at them. At that moment, I felt like, if I make a wrong move, they’re going to draw their weapons. It was 20 minutes after my set. Last year was cool, it was a big audience and they were really into it.

When are you happy?

salute: When I know the people who are important to me are doing well. Quietness makes me happy. Good music.

You stopped making music during the pandemic.

salute: A couple of months before the pandemic, UK Garage picked me up and I had good bookings. When the lockdowns started, all that was gone. At the beginning, like a lot of other artists, I had a creative streak…and then winter came. The days got shorter, I was tired all the time, I was doing nothing but doomscrolling and looking at the current COVID numbers. I was staying in bed till two in the afternoon and I didn’t want to see anybody. I was really depressed. I’ve never had it that bad before. I couldn’t look at my laptop anymore; I gave it away, locked myself in and drank and smoked weed. It was terrible. At some point I researched and found out that dark-skinned people’s bodies produce less vitamin D, so I started taking that and it helped.

And then?

salute: And then, one day, I started making music again. I needed it so badly. Soon afterwards, I finished “Jennifer”. I have to say, I make my happiest tracks when I’m sad. Before “Honey”, I was mourning my grandparents – I didn’t know them that well; it was more about what it had done to my family. So much came to the surface. Before that, someone in my extended family died every year; I made that track at the end of 2018, in two or three hours.

You went to church a lot with your family.

salute: Every Sunday. My parents are Pentecostal. Nigeria is a very religious country, both Christian and Muslim. The Nigerian community in Vienna goes to church a lot too. I was in church every Sunday. There, you hear that you’ll go to hell for having sexual thoughts about other men. As a bisexual man…I knew people who were gay when I was a teenager, and I thought, why do they have to go to hell? That’s when I started questioning all of it.

When did you start making music?

salute: Drum’n’bass was my first love. I was introverted as a child, and I spent tons of time making tracks on my parents’ computer. Music was an outlet for me. I wanted to start a second project making hip-hop instrumentals, and at the same time I was listening to James Blake and Sbtrkt and Rustie. Then a blog picked up on my Aaliyah remix, and pretty soon after that Trishes from FM4 wrote to me for an interview and they started playing my music. I DJ’d for the first time when I was 17; a few of my classmates showed up.

Have you reconciled with your Sam Smith remix?

salute: I was making a lot of remixes at that time. Somebody from Capitol Records wrote me, probably because they were hoping to get a cheap remix out of it. That was crazy, my Sam Smith remix ended up on a release with the house legend MK. I hadn’t found my sound yet, it was almost midnight, and suddenly, Flume released a new remix. I was just nervous. And I thought, why don’t I just make something like that? It came out okay. The A&R from Capitol was even in Vienna and wanted to manage me, but that didn’t work out for very long. The remix was my first big moment in Vienna – it seemed like everyone had heard it.

How do you strike that balance between function and innovation?

salute: I know how club tracks work, how they’re structured. As long as you’ve got that structure and the right sounds, that’s all that matters. You can be much freer with everything else. Music that produced to be technically perfect can be really boring; the vibe is often much more important.

Do you still worry a lot?

salute: I’ve gotten a lot more relaxed about my music and my career, because I’ve been through a lot. Nothing scares me anymore. That sounds cocky, but I really have had it tough. My family didn’t have any money. I went to England by myself because I wanted to be close to London, but it was hard. I was really broke for a long time. It gradually got better over eight years – it happens very quickly for some people, but not for me. But I’m almost glad.

At the same time, you released a lot of impressive music.

salute: It always looks better from outside. I was never satisfied; I jumped from genre to genre, it was an identity crisis. I didn’t match any line-ups. Festival bookers look to see how many tickets you can sell. The Soundcloud and Spotify streams didn’t translate for me. It went okay, but I wasn’t happy.

And then you moved to Manchester.

salute: I was there with my roommate for a Warehouse festival where I was DJing. The next day, we hung out in the city, hung-over. It’s crazy how cheap everything is there. And I thought, why don’t we move here? And six months later, we did. Karma Kid and Bondax were there and we shared a studio. It was a golden age for me.

You have an inclusion rider in your contracts. Why is a minimum level of diversity in line-ups so important?

salute: Because then the audiences are more diverse, and the vibe is better. You discover new music. A lot of times, the program consists of ten straight white dudes – that’s not bad in itself, but if they’re boring, then it’s bad. After one particular bad night, I talked to my agent about what we could do about it. A couple of people in America already had these inclusion rides, and I took some elements from them. Good support acts are so important for the flow. It’s worked pretty well up till now. The year before, I was still accepting every booking. But as an artist, I want to help get promoters to make a little more of an effort. It’s just fairer.

You don’t stay silent, even when it could hurt you.

salute: When I see something that’s not right, I say something – before another woman gets harassed, or when a DJ thinks he’s allowed because he’s been in the business for twenty years. If we really want to get rid of racism, sexism, homo- and transphobia, we have to start somewhere. What are these gatekeepers going to do to me? I only want to play places where I won’t be blacklisted for helping people anyway. Talk is cool, action is better.

“Everyone knows it, but no one talks about it.”

salute: A lot of people earn their money with music, but they don’t love music. A lot of lying. Drugs and alcohol are a huge problem too, and no one wants to talk about it. Drug use is out of control. And the things that happen because of it are crazy. So many talented people destroy their lives with it. A little bit now and then, cool. But there are people who are on stage every weekend who are clearly strung out, and the promoters are scoring them cocaine and ketamine. They’ll do it as long as they turn a profit. And when you stop making hits, you disappear. Music is my greatest passion…but something like that is just depressing.

What does it mean to have a feature in DJ Mag or a spot on Boiler Room?

salute: It’s a big compliment. After Boiler Room, my bookings went through the roof; when people see how you DJ, it makes it a lot easier for promoters. It can totally change your career.

“salute, 17 years old, with an Afro, from Vienna?” [a quote from an earlier interview]

salute: Ah! I’m from Vienna, but I live in Manchester, and I’m 27, with dreadlocks. I’m a lot more confident and more satisfied with myself and what I do.

Has it been hard to stick to making music?

salute: (thinks) There’s nothing else I want to do. Whatever it costs me – time, peace of mind – I need it. Otherwise, I’m not happy. There’s nothing I want more than to make art, to make music.

Stefan Niederwieser

Translated from the German original by Philip Yaeger.