Using language as a vehicle, the keyboard instrumentalist, composer and instrument maker GEORG VOGEL breaks down everything dear to him. Being attached to and alternating between playing and writing, he draws his material from multiple musical traditions and by doing so got involved in the construction of instruments and tonal systems, as the one-year scholarship holder for music of the province of Salzburg in 2019 explained in an interview to Sylvia Wendrock.

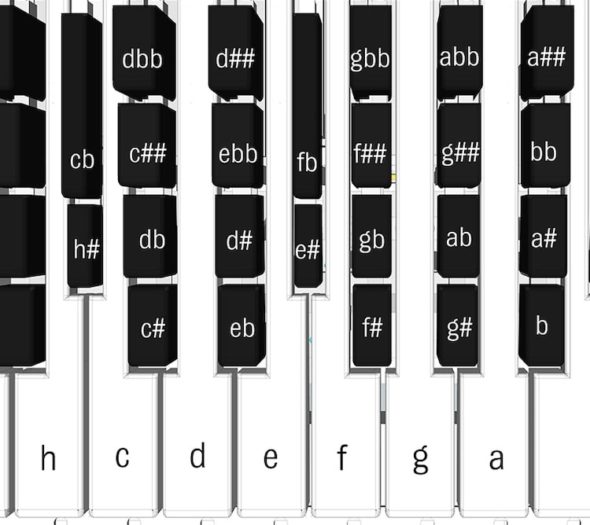

You are 31 years old and recently received a one-year scholarship from the Salzburg province for your octave of 31 notes. How did you come up with that?

Georg Vogel: In the meantime I’m already 32 years old, this being said as an aside only. The idea is already very old. There were theoreticians in the 16th and 17th centuries, for example, who wrote treatises on it and used this tonal system because it was based on what is believed to have been the most widespread temperament for keyboard instruments at the time, namely the mean-tone temperament, in order to be able to transpose further or to extend the tonal range tonally.

Would you see your music as belonging to spectral music?

And you espoused that approach…

Georg Vogel: … from the tuning practice, that is, tuning a piano yourself. With the piano this is a more complex process, so that there’s also a separate profession for it and most pianists do not tune their own instrument themselves When a string broke on my clavinet this was a welcome circumstance for me and at the same time an introduction to the many questions and also the other possibilities of tuning twelve keys. I wanted to proceed by ear and found pure tunings and the mean-tone quarter-comma temperament. I then specialized in them and let them become the starting point for having necessarily more than twelve tones in the octave.

But the temperament is still based on hexachords at the beginning?

Georg Vogel: Yes, this hexachord division is a navigational instrument in the diatonic space. By the clear denomination with help of the hexachord syllables the current location in the diatonic range is indicated. For example, the surroundings of a “B” can be defined in contrast to an “A sharp”. The enharmonic change here is then an enharmonic pitch change.

Do major and minor then still play a role, as they were originally derived from the hexachords?

Georg Vogel: In principle, all tonal aspects known from the twelve tones can also be found in the 31-tone system, the keyboard can be nicely derived from the further on transposed tetrachords and hexachords. However, they sound somewhat different there because the interval intonation is different: The major third is pure and the fifths are tempered. Thus major/minor tonalities then get a different weighting and, due to their altered tone quality, can be used differently in composition and improvisation than with twelve equally tempered tones.

How do you proceed to the 31 transpositions?

Georg Vogel: In the tuning process, first the white keys and the first row of the black keys are tuned to enable some transpositions of the major and minor triads. And then the transposition is continued on the basis of the quarter-comma temperament, so that further minor and major thirds result and the circle of fifths is extended. In doing so the number of tones between the notes increases and then there is a possibility to close this chain of fifths at the double # and the double♭and thus create a transposable tonal system. The enharmonic change thus takes place much further back in the string of fifths. Aisis, for example, is then almost the same as Ceses. And then there is the additional trick of distributing this difference to previous tones, and in this way one can create a tonal system of 31 tones, which is approximately congruent with the quarter-comma temperament, which at the beginning can only be tuned by ear.

What makes it so attractive for you to restrict yourself to the hexachords, i.e. a structure, on the one hand, and to look for something new within it at the same time?

Georg Vogel: The small units are modules that can be plugged together in the most diverse and infinite possibilities. And the search for smaller building blocks led me to the tetrachords and hexachords, which are actually intertwined tetrachords. It’s an approach that is used in my compositional work.

To search in the realm of small and on a small-scale …

Georg Vogel: … is the sober need to find something through which emotional access can be built up at all. When something is taken apart, there are different ways of docking on somewhere, different ways of putting it together. I am looking for parts that can be dealt with and that also implicate needs to use them, to play with them. To organize them in a way that it feels good.

I’m using these tetrachords as part of diatonic improvisation and composition techniques whereby diatonic here means something different than just the white keys, namely due to the tones, i.e. due to the hexachord and due to the transpositions that result from it. This is then also the actual key for the further expansion of this tonal system, which can include dia-tonal aspects.

Another one is the spectral approach to intonate chords, which can also have a tonal definition, differently, depending on which overtone range I want to simulate, because the 31-tone temperament is only an approximation of the just temperament.

One can also see that a most precise questioning of the terms already leads you to your ideas and approaches, which is also confirmed by your trilingual web presence. Yet you describe all the three languages used as artificial languages … as a reference to language as a mere tool and vehicle?

Georg Vogel: Language is formed and constructed. Artificial language here means that it is a product of the shaping that language undergoes. There is obviously a need to shape language forms through cooperation, influenced by political, economic and other factors. This is why I have tried to realize a radically phonetic approach with the third artificial language which tries to spin grammatical guidelines consequentially further and to apply them to the current sound state which I also indirectly retain. In other words, not so much a writing system for a language as a norm for textualisation.

“HOW CAN SOMETHING I’M ADDRESSING BY THOUGHT BE IN TOUCH WITH THE ASSOCIATED EMOTIONAL CONNECTION?”

Isn’t composed music then, as a language understood in this way, a textualised form?

Georg Vogel: Exactly, there are many overlaps in dealing with sounds. Writing systems and visualization systems are simply a tool and, to a certain extent, also neutral. They can be used and also have a certain momentum of their own. I am very much interested in the interactions between structures and feelings, between conceptualization and direct experience. How can something I’m addressing by thought be in touch with the associated emotional reference? And is the emotional reference or the thought there first? I often use the rational aspects to mark out a field and try to find within that field structures with which one has an emotional connection. To proceed further in this awareness of partial aspects and to limit the area in which one is searching.

Are reason and emotion opposites for you or do you analyze emotions using rational concepts?

Georg Vogel: Both. They can be opposites, want different things, want the same things. The desire to build up a framework supported purely by reason also arises from an emotional motivation resp. to present something quite systematically corresponds to a need too. One could list all the world’s possibilities. But a selection is made of what can be listed in categories quite well or where attempts are made at all to crystallize describable forms, and that comes from a certain emotional stimulus. Although it is not directly tangible, yet it describes again and again this tension and the question of where things are going.

How did the production of own instruments come about?

Georg Vogel: In the beginning was the clavinet. An electro-acoustic clavichord from the 1960s, basically a simple construction made of strings and pickups. I dared to analyze how it worked and based on this to consider the possibility to develop a multi-tone, i.e. 31-tone instrument similar to it. During this process some instruments have been created, not all of them in accordance with my original intention, but all of them with at least 31 tones within the octave.

And which ones are there now?

Georg Vogel: The digital M-Claviton was first produced two years ago, now there are two. This year another, electric claviton will be presented: a real string instrument without digital sound generation, conceivable like an electric guitar with keys.

By the way, the term claviton is a contraction of the name of the only surviving 31-tone keyboard instrument with this division of the keys: the Clavemusicum Omnitonum from the early 17th century.

“TO FIND A COMPOSITIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR THIS IN ORDER TO THEN IMPROVISE WITHIN IT IS VERY EXCITING!”

Which interactions do you see between composition and improvisation?

Dsilton is the resulting project.

Georg Vogel: Yes, for many years David Dornig and I have been working together on it, for several years now we have also been a trio with Valentin Duit, with these 31-tone instruments and drums. In this band we’re playing arrangements and compositions both by David and me.

I’m fascinated by how the new things I’m getting involved with and the way I’m dealing with them influence each other, resp. how getting involved is accompanied by its own momentum that was not foreseeable before, and how this changes ideas and ways of proceeding.

Our first album is in the works and will probably be released this summer.

Do you also encounter this “new thing” in the interplay of the group?

Georg Vogel: By exploring together and also intensively entering into the process of working out compositions and playing concerts, undreamt-of things come to light. Dsilton has some common denominators for all compositions. Regarding rhythm, it’s a modulation concept based on so-called n-tuplet time signatures and basically the 31-tone tuning that all compositions use. The rest is very varied and goes in all possible musical directions.

Other current ensembles are for example Flower, my long-time trio with Raphael Preuschl on bass and Michael Prowaznik on drums. A new project is GeoGeMa, a trio with Gerald Preinfalk on saxophone and Matheus Jardim on drums, where Gerald Preinfalk writes the compositions and we then deal with them in a very improvisational way. There the M-claviton is used for a quarter-tone tuning. We have just presented our first album at the Rhiz. And also the trio Tree with Andreas Waelti (double bass) and Michael Prowaznik (drums) and myself at the grand piano with a slightly different musical orientation. The last album is called “Between a Rock and a Hard Place” and was released last year.

In “Ivan Baanas” you are cloning yourself.

Georg Vogel: In the video an imaginary partner is sitting next to me with whom I play this four-handed piano piece. That is of course me. The special thing about it is that two voices are very present upfront and many voices tag along in the background very quietly – so it’s realistic to play this at all when divided between two performers. The piece has a 31-tone temperament and the instrument is a simulation of a fortepiano, a type of piano that differs from the massiveness of the concert grand piano in that it has less tension and a brighter tone, it’s quieter. There are many intermediate stages in this process of building a grand piano which are very interesting in themselves for to imagine what it would be like to have a 31-tone instrument on this basis. Just like with the fortepiano. On the one hand it is technically possible to build such a 31-toned instrument, on the other hand I am playing a digital approximation in the video. In addition there is evidence for these early pianos that they had unequal temperaments, partly also in the mean-tone range. This enharmonic difference was also used quite deliberately in many compositions from that period. Therefore it is very exciting for me now to return to this point and to work on issues that are still outstanding for me.

Like what?

Georg Vogel: If the enharmonics are taken into account, if it also has tonal consequences and if it makes very good sense in terms of sound and has been done to tune pianos in different temperaments. Some of these considerations are included in “Iwan Baanas”.

Baanas in this case corresponds to the Parnass, the whole title to a trespassing of the mountain of the muses. The aspect that “both” performers are playing the chord or the ornaments, etc. at the same time is related to the fact that the whole piece is concretized metrically. Each note has its strongly fixed value and there are many modulations. It’s a fully-composed solo arrangement in both metre and tone; an arrangement for Dsilton is in the making.

The current situation has serious consequences for the art and culture industry. How do you feel about that?

Georg Vogel: As with many colleagues, there are many cancellations and postponements, including a trip to Zagreb with GeoGeMa or concerts with Tree in Vienna and Budapest or the Dsilton concert in Salzburg. Until the resumption of concert activities, the focus is now more on the development of programs, on composing and on the completion of the new type of Claviton in addition to the planning of another digital model and further work on an acoustic instrument. It’s not easy to assess which decision-making dynamics will still evolve from politics. In any case, we should all be vigilant as affected parties, especially with regard to encroachments on personal liberties. The crisis makes it clear that we are actually (and have been for a long time) dealing with only one public sphere in the world. In order to better respond to this situation, a much greater degree of solidarity and cooperation is needed. In addition to the great diversity of confronting a pandemic for people in different places in the world, the causes of the global spread of diseases should be considered and investigated more closely. This also results in many overlaps with the other burning issues such as fair and just distribution and sustainability in relation to natural resources.

Many thanks for the interview!

Sylvia Wendrock

Dates:

All dates until the end of June have been postponed or cancelled due to the Corona crisis.

Links:

Georg Vogel

Translated from the German original by Julian Schoenfeld