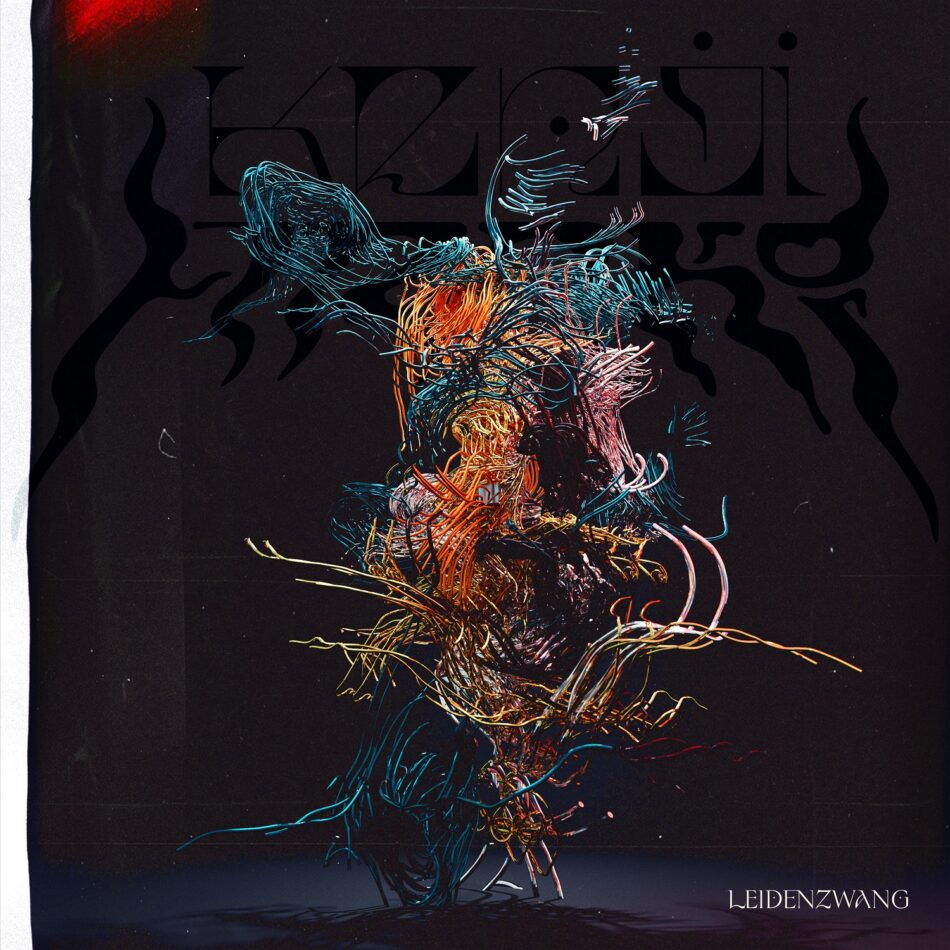

With “Leidenzwang” (Affine Records) digital artist KENJI ARAKI releases arguably one of the most compelling positions on the state of advanced electronic music, between dystopian post-club exploration, aural body horror, dented retro fragments and extravagant breakcore elements. The fact that there is a specific pop sensibility behind it makes the music, despite all complexity and intricacy, an exciting future sketch, beyond conventional experimental and pop impulses. Didi Neidhart met with KENJI ARAKI for an in-depth conversation.

The album starts with the track “Avant”. Translated, this can mean, among other things, “before”, “prior”, in sports lingo, also “attack”. The dark atmosphere with the jungle beats reminded me a little of a kind of alien birth. What was your inspiration there?

Kenji Araki: I’ve always been a fan of explosive album intros. The specific inspiration in this case was Kanye West’s “On Sight” from his industrial album “Yeezus.” Tracks like this show that an album doesn’t need a lengthy intro. This approach simultaneously embodies the album’s directness and confrontational nature. It also hopefully signals the uncompromising nature of the album from the start. I actually find the idea of alien birth very intriguing. You can definitely argue that “Avant” represents the birth of the sound world of “Leidenzwang” (“Suffering Compulsion”).

Where do those deep jungle basses come from, for you? They sound more like darkcore/techstep, as fabricated in the 1990s by labels like “No U-Turn Records”, “Metalheadz” and acts like Ed Rush and Goldie, and hardly at all like current dub or brostep basses.

Kenji Araki: My first great love in the world of electronic music was UK dubstep acts like Benga, Coki, Burial, Skream etc. I always had an affinity for dark, heavy sounds. As a former almost exclusively rock and metal listener, the world of the UK bass music scene offered me all these facets in one package, which was also combined with my fondness for technology. However, current dubstep acts have also been part of my musical diet for quite a few years. These influences may not be as concretely audible in my sound design, but they absolutely influence the aggression and climax of my music.

There are also foggy dub sirens on “Matter” that are definitely reminiscent of Burial. There is also a certain kind of melancholy running through the album that kept me thinking of Burial. Moreover, the tracks are structured in a similarly fragmented way and have this dark, also very cinematic continuous rain atmosphere. Do you agree with this assessment?

Kenji Araki: Like so many, I am a huge fan of Burial’s music. The kinematic energy, textuality and atmosphere of his music have unmistakably shaped my understanding of music. Furthermore, the emotionality of his music is what makes it so good in the end. It’s not a tech demo like so many released club tracks. It’s an emotional, empathetic, human experience.

“HAUTE COUTURE RUNWAYS ARE A BIG INFLUENCE ON MY UNDERSTANDING OF VISUAL REPRESENTATION AND INSTALLATION.”

The promo text for “Matter” also states that it is virtually the soundtrack to a “dark fashion film.” How do you come up with such an idea? Is fashion important to you or is it more about the dark side of the glamour world associated with it?

Kenji Araki: For me, fashion is simply another medium for artistic and personal expression. Specifically, haute couture runways are a big influence on my understanding of visual representation and installation. I actually see a lot of parallels between haute couture designers and modern electronic musicians. The designs that are seen on these runways are not something we will see on the street in a small town anytime soon. However, the developments that emerge will be reflected in everyday fashion a few years later.

“Leidenzwang” is my haute couture statement piece in that sense. It is not for everyone. It doesn’t try to be suitable for the masses. It specifically tries to look into the future to offer suggestions or predictions, so to speak. In any case, I can’t wait to present my idea of post-Leidenzwang-pop to the world, which is really ready to accompany people in their everyday lives, in my opinion.

What importance do vocals actually have for you? Are they real voices, i.e. voices that have a body or are at least looking for one, or are they more like digital files that are then used, like on Burial or especially on Footwork/Juke?

Kenji Araki: The human voice is, and remains, my favorite instrument. For me, it is the most complex, expressive synthesizer of all time. Its time- and frequency-based modulation possibilities are very broad. In addition, of course, there is the empathic component. When you’re working primarily electronically, I think it’s important to let a touch of humanity shine through. Otherwise the connection is missing. As technical as my music may sound in parts, in the end it should remain a human, empathic experience.

The voices that appear are a melange of actual recordings of my own voice, other singers, and samples with a variety of different sources that, when listened to closely, illustrate a place or scene.

In the beginning of “Nabelschnurtanz” there are these female vocals that seem to crawl right into your ears, reminding you a bit of Billie Eilish, but pretty quickly it becomes clear that the beginnings of a pop song are more of a trap here, as well. Because what follows is rather a roller coaster ride through metallic meat grinders. However, I had to think not only of horror films like Dario Argento’s “Suspiria” or the body horror of “Hellraiser””, but especially of Japanese horror classics like “Ju-on: The Grudge” with which the so-called dead wet girls were introduced into the modern horror film iconography in 1998. Do such references play a role for you or are these Japanese clichés that I’m imagining?

Kenji Araki: I always find it super exciting when elements of pop music are applied in a boundless context. The directness and interpretation for maximized effectiveness form a very effective contrast to the freedom and curiosity of experimental music. Pop structures in themselves are a prime example of effective experience design. As listeners, we have already absorbed the rhythm and pacing of a pop song so strongly into our collective consciousness that we immediately prick up our ears at unexpected deviations. But this only works if you play with the audience’s expectations. You present an accustomed concept and let the listeners acclimatize before, as you so beautifully put it, sending them on a roller coaster ride through metallic meat grinders.

“Nabelschnurtanz” specifically, however, is a pop song through and through in my opinion. While the sounds and rhythms chosen are atypical of the genre, the structure and intention attest to them. Furthermore, I do not define pop music by any genre tropes such as certain sounds, rhythms, and lyricism, but by its goal. Pop music, by definition, seeks to be popular. That doesn’t necessarily mean that every pop song should end up in certain charts, but pop music is always designed to be used by consumers as a medium of entertainment. This is definitely true for “Nabelschnurtanz”.

“I’M CONVINCED THAT YOU SHOULDN’T CLOSE YOUR EARS TO ANY GENRE OR MUSICAL ERA.”

How do you actually feel about the past? On “Gel & Gewalt” there are grunge samples, but they also seem to somehow run out of life energy, and on “Monomythz” the ‘2000s-Eurodance aesthetic’ is also more or less put through the wringer, or subjected to a moose test. Is the past for you a “Stranger Things”-retro-space or is there still something to take there – even if only in ‘dented’ form?

Kenji Araki: I grew up like many with a varied diet of different guitar music. Played in a few bands, none of them particularly successful; but educational. I am convinced that one should not close one’s ears to any genre or musical era. I have little interest in being a genre revitalist; there are enough acts doing that. However, I am constantly consciously or unconsciously pulling elements from music of the past. If those elements then show up in dented form, it’s solely due to my curiosity and drive to constantly find new musical territories. Sometimes this works out better, sometimes not so well. But that is the core of experimental work. You just have to dare to do something terrible. Once you let go of the pressure of wanting to make something good all the time, with a little patience, it usually happens automatically.

How important are sound transformations or mutations for you – for example on “SINEW”, where I can just barely make out the distorted double bass from the promo text – and what is the challenge there?

Kenji Araki: Unlike many other musicians, I don’t really care about the origin of a sound. Facts like the bass sounds being manipulated by double basses could be exciting for listeners, that’s why it’s mentioned. However, I am always concerned with the final product. The process is constantly changing and the frequency of sound transformations and mutations can be attributed to curiosity and the desire for auditory development, as stated previously. To answer the question though, in certain situations sound manipulation is essential, but, in others, the nakedness of an unprocessed sound speaks for itself.

You describe yourself as a digital artist. Why is this designation so important to you? By now, most electronic music is made digitally.

Kenji Araki: I like the term digital artist because it doesn’t draw boundaries between different digital creation processes. The way I work in 3D programs like Blender is very similar to the way I work in audio programs like Ableton Live. So, for me, it’s less about the distinction between analog and digital work. I also regularly use analog equipment like acoustic instruments, analog synthesizers, etc. – but with the interdisciplinary possibilities that digital offers. Nowadays, anyone with a laptop and a few programs can immerse themselves in a variety of creative disciplines. Once you develop a sense of UI/UX design, it’s not difficult to jump between mediums and unite them.

How would you actually describe the relationship between the beats and the sounds in your tracks? You have a remarkable amount of beats that inherently want to get going, but start off as hard as broken tractor engines. There are breaks, drops, but then no “redemption.” Electronic artist Fatima Al Qadiri once described the dystopian nature of her music in terms of the lack of utopian beats. Do your beats possibly also no longer find their way to a dancefloor or only to “haunted dancefloors”?

Kenji Araki: I love beats! It’s probably also the compositional part that comes easiest to me. That’s why they bore me quickly, though. Continuous 4/4 rhythms often lose tension in my ears because of their predictability and repetition. However, when rhythms are just hinted at, broken up, or partially left out altogether, the brain fills in the gaps and those moments of creativity in the audience make it exciting for me. It also helps me design a track more as a journey with turns and surprises and U-turns. A continuous dance rhythm, however, almost demands structure and order. A comparison would be certain sounds used in film. A sword, as expected, has to make that typical “swish” sound, otherwise it wouldn’t feel “right” anymore. So we’ve all been collectively conditioned by repetition. It’s similar with genre expectations, especially when a beat occurs. But that’s not meant in any judgmental way, the detachment from expectations was simply the driving force behind the album.

Your label nicely describes your music as “post-club exploration with a pop sensibility,” and about the track “lluviácida” it also says that it’s “inspired by the rave scene observed from afar.” How much are such feelings related to the loss of something and distance from it, and to fundamental attitudes about it, and how much to Corona and its consequences? I’m thinking of lockdowns, no clubs and parties, a whole teenage generation without such experiences.

Kenji Araki: I grew up far away from any club scene on the countryside. So, with the exception of fourth-rate drum-and-bass records and David Guetta remixes in the village disco, I could only experience club music through the Internet and hearsay. I’m convinced that I idealized and romanticized the whole thing as a teenager. But these feelings have been part of my identity for a long time. Beyond that, of course, I’ve also picked up the legends of certain rave scenes over the years, like the ones in the UK and Berlin, and had dreams of being a part of them one day. It provided an imaginary sanctuary and destination for me at a formative time, which is increasingly turning out to be a beautiful Sisyphus task. The lockdowns brought those feelings back, but this time in a different context. At the time, I was living in Vienna, a place that could have offered me what I had dreamed of for so long, at least to a large extent. Instead, I just sat at my computer every day and did the same things I had done when I was 16. Ironically, this probably created a common thread. I was back to being a daydreamer and voyeur on the outside looking in.

How did you actually come up with track titles like “Nabelschnurtanz“ (“Umbilical Dance”), “Gel & Gewalt“ (“Gel & Violence”) or “Leidenzwang“ (“Suffering Compulsion”)?

Kenji Araki: I think word-creations are great because they offer so much room for interpretation. “Leidenzwang” (“suffering compulsion”) for example, is a combination of the words “Leidenschaft” (“passion”) and “Leinenzwang” (“leash requirement”). The artistic creative process can often be one of self-flagellation. The German language and the word Leidenschaft (suffering creation > passion) are not particularly subtle about this. At the same time, however, it’s almost like an addiction. You’re constantly chasing the next high that offers artistic fulfillment, so you’re forced onto a leash. “Umbilical dance” is a synonym for life for me. You’re born, you disconnect from the umbilical cord, and then you dance until it’s over. For now, I’ll deliberately let the audience decipher the title “Gel & Violence.”

“FOR ME, CONFRONTATION IS THE ANTITHESIS TO ESCAPISM.”

The promo text talks a lot about obsessions, about passions and about confrontations, but also literally about “self-flagellation” and an associated purifying catharsis. How can all this be translated into electronic music? Or do you approach it in a similarly expressive way like, for example, with various types of metal?

Kenji Araki: For me, confrontation is the antithesis of escapism. That’s why many of the melodies and rhythms on the album are deliberately inaccessible. I try not to keep the listener on a leash. I try to confront them with auditory border phenomena to possibly let new synapses form. In my music, the self-flagellation process and the associated catharsis are less related to playing styles like metal or performative noise music, they are more related to the lengthy process of artistic self-discovery and eternal experimentation and trial and error. My fingers don’t bleed because I play too much drums, but my brain does, because I’m constantly searching for development, and this can only be found through consistency, obsession and patience.

But now the album has twelve tracks with a playing time of 50 minutes, and because of the mentioned obsessions, a not unimportant question arises: How do you stop yourself from being guided by your obsessions, only, and ultimately structure the tracks, or determine how long they are in each case? You could also lose yourself in it and go more in the direction of ambient, noise, drone with correspondingly long tracks. How does it come to these condensations?

Kenji Araki: Twelve tracks, 50 minutes was the goal from the beginning. Here you can clearly feel the influence of pop music again. I’m just a big fan of compact, effective music. Of course, I could also do 30-minute drone pieces. But on the one hand that doesn’t fit my personality, I’m too busy for that and, on the other hand, it offers a challenge to put elements of the ambient, noise, drone and experimental scene into a pop outfit. These combinations are what have always made me bright-eyed. I also find that certain formats are better suited for live settings. However, from the beginning, I wanted “Leidenzwang” to be an album that could just as easily be enjoyed in a club as on a train ride.

In 2021, you were among the winners of Salzburg’s “Elektronikland” award. What did that do for you?

Kenji Araki: It was an absolute honor to be one of the award winners. Besides the obvious benefit of the cash prize, it was also a nice sign for me that the province of Salzburg can have open ears for music that tries to be progressive and is not looking for direct, immediate success. Moreover, it’s always nice to be able to present an award to parents who hang it up with pride!

Will there be a tour to go with the album?

Kenji Araki: Absolutely! [Note: See summer tour dates below.]

Live, your music is supported by atmospheric videos. In addition to many body horror references, there are also those to particular anime styles, but also, at times, downright dark psychedelic elements and nightmarish encounters with dolls. How important are these visuals and is there perhaps some interplay between them and the sounds?

Kenji Araki: I’ve always been a fan of good audiovisual performances. The body horror touches, psychedelic elements and anime stylings come about almost automatically through the collaborations I’ve made over the years. I just naturally gravitate towards a certain aesthetic, hopefully creating a visual thread. I find specific elements such as the nightmarish encounters with dolls, for example, exciting because of the inherent dichotomy between childlike innocence and horror. Basically, these interactions are always part of my work.

Thank you very much for the interview!

Didi Neidhart

Kenji Araki Live DATES

04.06.2022: Heart of Noise, Innsbruck

05.06.2022: Album-Release-Party, feat. Zanshin, Fluc Wanne, Vienna

24.06.2022: Rockhouse, Salzburg

01. oder 02.06.2022 : Sonic Territories, Vienna

23.07.2022: ImPulsTanz Festival, Vienna

30.07.2022: Popfest, Vienna

05.08. – 22.08.2022: Residency am Yppenplatz (Der Goldene Shit Agency), Vienna

Links

Translated from the German original by Arianna Alfreds.