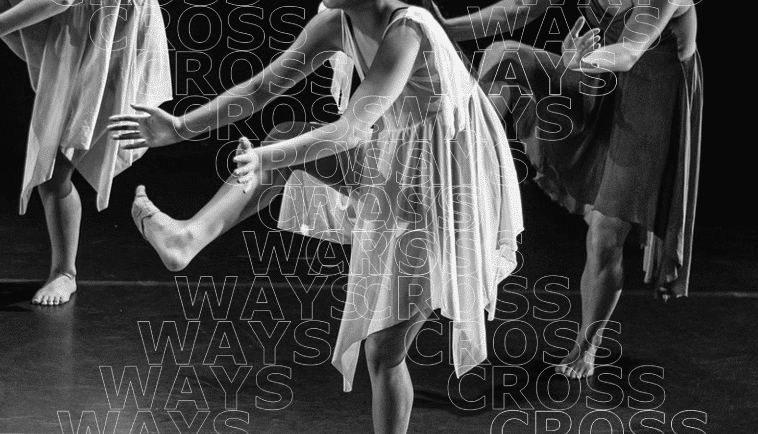

Following Part 1 and Part 2, the third and final segment of the CROSSWAYS IN CONTEMPORARY MUSIC: CHOREOGRAPHY & DANCE series sets out on the trail of new and upcoming works that unite new music and choreography & dance.

JUDITH / CUT_FADE

For composer Judith Unterpertinger, who dismantled a grand piano for her works (“Piano Sublimation”) or was inspired by holes and irregularities in London walls (“Wall Studies”), the focus is on the relationship between the arts. As an instrumentalist, she performs under the name JUUN and plays in ensembles of various kinds – from delicate improvisation to industrial and noise.

With choreographer Katharina Weinhuber, with whom she is also active as the duo znit, she has a long-standing collaboration, which resulted in the dance opera “JUDITH | Schnitt_Blende” (Neue Oper Wien, 2015). For this, the two, who describe their working method as a dialogue, shared the directing. “We’ve been working together for a very long time, we know what comes from each other’s sides, whether it’s on the part of the choreography or on the part of the music. […] Overall, we have found a common language,” Katharina Weinhuber explains in a mica interview. It was a conscious decision not to entrust another third person with the direction.

“OVERALL, WE FOUND A COMMON LANGUAGE” – KATHARINA WEINHUBER

In great contrast to classical opera, the piece has no narrative storytelling, even though some of the source material for it was very personal; not only is the composer’s first name Judith, but her grandmother, who suffered from dementia, had the same name. All of this flowed into the creation of the dance opera, for which the directing duo Unterpertinger and Weinhuber interwove three female characters. Unterpertinger explains: “From my research material on my grandmother, Judith, the biblical Judith figure and – as a counterbalance – a contemporary figure, I gave the musicians involved visual and text material. I asked them to improvise short fragments of ten seconds to one minute on this. This served me in part as a starting point for the composition.” As a composer, one usually works from a distance, whereas as a choreographer, one is per se more involved in the process and develops the piece with the dancers. For their collaborative work, this division was broken down, “because, for example, during the composition process, I already make a sound recording of fragments that are already finished. That’s a luxury and usually not affordable.” The recordings were then used to continue working on the choreography and the overall staging. And these parts of the choreography or staging, in turn, influenced the composition.

Collective work needs a certain openness. Strongly hierarchical structures, such as can sometimes be found in the independent music scene, can also hinder this process. For Judith Unterpertinger, it must be clearly defined from the beginning who has the final artistic decision in which area.

INTERACTIONS

This processual, free work in the collective is also described by Pia Palme in connection with her work “Wechselwirkungen” (“Interactions”)(2019/2020), co-produced by Wien Modern: “… we worked with each other, without the fixed sequences and hierarchies of the institutions. The music was not finished first in ‘Wechselwirkung’ so that the choreography, direction, etc. could then come. For a free form, the composition must be flexible enough. That works very well if you work with modules, and put them together in the form of a montage. I find that then the different disciplines also have more room to unfold and can mesh better.” As with Palme’s earlier work “Abstrial” (2013), a collective was in charge of “Wechselwirkung”: Juliet Fraser, Christina Lessiak, dancer Paola Bianchi, dramaturg Irene Lehmann and Pia Palme as composer.

“FOR A FREE FORM, THE COMPOSITION MUST BE FLEXIBLE ENOUGH” – PIA PALME

At this point it should be mentioned that “Wechselwirkungen” could not be made available to the audience live, but as a film, due to the corona regulations that were in effect at the time. The permanent changes in the regulations and related conceptual changes had an impact on the choreography and composition process. Nevertheless, “… with all the obstacles and effort, it became a very special production, the atmosphere was open and good, the ensemble brilliant, the collaboration intense and gratifying.” (mica interview)

WORK & GROWING SIDEWAYS

Choreographer and performer Brigitte Wilfing and composer and turntablist Jorge Sánchez-Chiong have been working together for many years. In conventional concerts, movement is secondary to music. This is not the case for Wilfing, who studies the musicians’ movements to produce sound and develops her choreographic material from them. Works by Jorge Sánchez-Chiong are known for breaking concert formats. The native of Venezuela and Viennese resident writes for classical instrumentation, electric bass or turntables; his music thrives on spontaneity, surprising turns and he, himself, moves in several scenes – from new music to improvisation, multimedia art and club.

“AS A COMPOSER, IN SUCH A CONSTELLATION, YOU ARE, FIRST AND FOREMOST, NOT A SERVICE-PROVIDER” – JORGE SÁNCHEZ-CHIONG

In terms of a synesthetic interest, their joint work, “Work” (PHACE & Wien Modern, 2014) stands out. The impulse for this was to create a situation from which dance and sound emerge simultaneously. The starting point was formed by various movement patterns and sound patterns that were expanded to work on an interpenetration of the disciplines. The content is – as the title indicates – about “work”. In the center is the work on the instrument – a cello is prepared, repaired, played. What patterns of movement are already present in the musicians’ playing or in the handling of the instruments, what can be expanded and reinforced? The attention is shifted to the fact that the sound production can also be experienced as dance and vice versa, the choreographed movement can also be heard as music. “As a composer, in such a constellation you are first and foremost not a service provider,” Jorge Sánchez-Chiong sums up. What is striking here is that the two only accept artistic results when the other is also satisfied with them in his or her own discipline. “No one compromises,” is how Brigitte Wilfing sums it up. Leaving one’s own field requires trust, and that can only be strengthened through exchange and communication. A large part of the work lies in communicating and responding to individual aesthetic dos and don’ts, explains Brigitte Wilfing, who is currently writing an artistic dissertation on choreographic composition, in a video lecture.

Finding new ways of sound production by changing one’s habitual orientation – this kind of perceptual shift is also used, for example, by the Situationists surrounding Guy Debord – with their call to deliberately get lost in foreign cities or to orient oneself there with the map of another city in order to have new experiences – is a source of inspiration for Wilfing and Sánchez-Chiong. How does listening to and playing music change when one is engaged with new coordinates? With “growing sideways” Brigitte Wilfing and Jorge Sánchez-Chiong – after “Work” and “Land of the Flats” – now present their third major production at Wien Modern. Together with the transdisciplinary Assemble andother stage, they initiate a collaborative work process in which they confront impossibilities. “Growing sideways” – the sideways movement – sets up the direction. This very unique form can be seen and experienced on November 13 and 14, 2021, as part of Wien Modern.

THE SLOWEST URGENCY

For Peter Kutin, a shared vocabulary and time for joint development also play key roles: “I think it’s important to allow time for joint development in collaborations, and to try to go very deep into the material and to exchange ideas about what we’ve experienced, to research. Ideally, this creates a kind of vocabulary that can be used to talk about the music developed for the piece and its affect, without the choreographer and musician talking past each other. It is incredibly difficult to talk about music or sounds – they are defined and perceived so differently from person to person – especially when they elude the staff or can no longer be represented with it and focus on timbre and abstraction. Therefore, I think it is a very important step to develop together through experience towards a vocabulary. That the participants appreciate each other and understand or know their respective artistic approaches is, of course, a basic prerequisite.” In addition to experience, Kutin – asked by the author for recipes for good collaboration – also describes respect and attention as essential. “And also that the urge to assert oneself has already set in. People who inevitably put their ego over everything and want to and have to take over everything, I find very troublesome, especially when it’s actually about cooperation, exchange and collective experiences and developments. But working with new artists and their teams is basically always like checking in on an expedition ship. Either we find new territory or we come back empty-handed. In the worst case, we suffer shipwreck.”

“WORKING WITH NEW ARTISTS IS BASICALLY LIKE CHECKING IN ON AN EXPEDITION SHIP” – PETER KUTIN

For “The Slowest Urgency” (Wiener Festwochen, 2021) he met with Philipp Gehmacher, an internationally renowned choreographer. The piece directs the audience’s focus, first and foremost, to the sense of touch, when the four dancers lie or squat on the floor and run their hands over it as if they were collecting sand. Can you hear the movement of the fingers stroking over it? Interestingly, the dance floor is made of felt. Choreography and music intertwine seamlessly, creating new worlds. Peter Kutin’s music creates atmosphere, sometimes meditative, sometimes mass-like, sometimes blindingly bright. In between, there is always space for silence. And space for the small movements. Peter Kutin creates with his composition and sound direction in “The Slowest Urgency” a soundscape in which the bodies move as if they always belonged. At moments when the performers wander, crab-like and negotiate, skeleton-like, with their limbs, there are clangs and buzzes on the musical level. Gehmacher, who is not on stage himself this time, hands over his dance repertoire to a new generation of dancers with “The Slowest Urgency.”

360° – SKINNED

For Lissie Rettenwander, working with dancers was something new at first – but dancing herself was not. For “360° – skinned,” which was performed at the 2021 Osterfestival, the Tyrolean-born dancer contributed the music together with Fabian Lanzmaier. Rettenwander, who experiments with voice and sound, uses everything possible for her works, from accordion, tuning forks and fabric singing birds to rooms and zither, and moves along the fine line between avant-garde and tradition. Her steps are well-considered. She describes the process of settling into the production process. “To move, that was what was most important to me from childhood and for a long time of my life. To move in freedom. Moving in nature. Now I was sitting on the edge of the dance floor during rehearsals, watching the dancing of the others, and together with Fabian Lanzmaier I was supposed to provide the music for this. The roles seemed clearly distributed, here the dancers, and here the musician. When I was called a musician, something in me bristled as if to say: ‘But I am also a performer.’ At the same time, I questioned the role of music. So I asked the dancers: what function does music have for you? One of the many answers that followed was ‘power’. I thought about that for a long time. I asked myself: does music give power, energy? Are we musicians energy providers or impulse providers? I couldn’t answer the question for myself yet, but I was glad to have asked.”

The production by choreographers Anna Müller and Eva Müller thematically emphasizes the uninhibited and the wild – works with visuals that takes place on a 360-degree viewable stage in Salzlager Hall. Lissie Rettenwander therefore thought it wise to keep her part pared down. She decided to use only her voice and small instruments that ornithologists use to imitate bird calls, although she should have played with her traditional instrument – the zither. “Fabian and I had set up our fur on the edge of the dance floor, at the transition between the stage and the audience. Like two guards. In the back the audience, in front of us the dancers, above us Beto De Christo’s light design. And we also had our appearance on the dance floor – as a bird duet. Then Fabian left and a second duet developed with the dancer Emmanuelle Vinh. She moving. I, moving and acting with my voice. What a beautiful experience. I went off again and sat back with Fabian on our fur and was again the musician at the edge of the stage. The edge as a wonderful place of boundary.”

“WHEN I WAS CALLED A MUSICIAN, SOMETHING INSIDE ME BRISTLED” – LISSIE RETTENWANDER

At Wien Modern 2021, Lissie Rettenwander is now in the program with a solo project. Again, reduction is the theme when Rettenwander plays the foyer of the new mdw (The University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna) Campus Future Art Lab with only her body and her voice. Sometimes only the human body with its acoustics are enough to create a new piece of music theater.

Winfried Ritsch, who once contributed the sophisticated algorithm for “Maschinenhalle #1”, is represented at Wien Modern with the walk-in sound installation “The Song of the Organ”. Lissie Rettenwander will set the algorithmically-generated composition in motion with her voice. In the work for robotic room organs and singer, man and machine are networked in such a way that the computer organ will imitate the singing and repeat and vary it in loops over the following days. The sound experience will again end with a vocal performance during the closing event.

Ruth Ranacher

Links:

Translated from the German original by Arianna Fleur Alfreds

Crossways in Contemporary Music

Crossways in Contemporary Music: Choreography & Dance – Part I & Part II