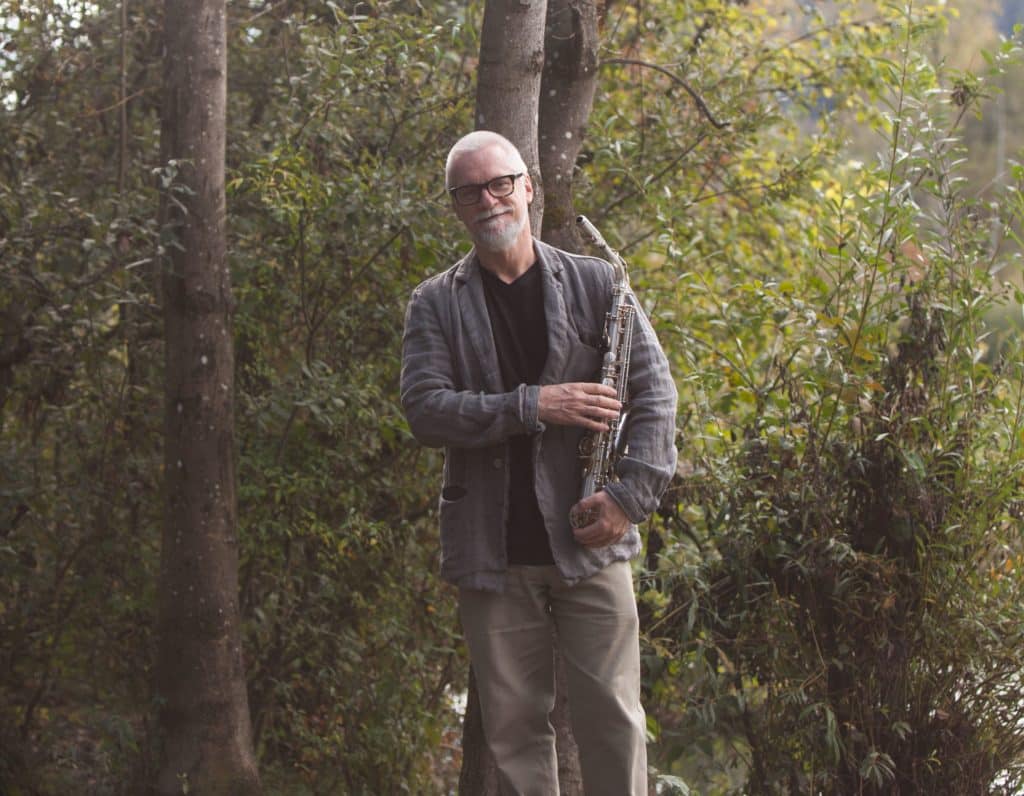

Wolfgang Puschnig is a leading figure of the European jazz scene. He was a founding member of the Vienna Art Orchestra in the late 70s, before performing with Carla Bley, Steve Swallow, Jamaaladeen Tacuma, and a long list of international jazz legends – if we’re being honest, he’s something of a legend himself. In 2022, he received the prestigious Culture Award from his native Carinthia; in his presentation speech, Porgy & Bess head Christoph Huber described Puschnig as a “musician of the world, able to move successfully between all musical worlds.” In this interview, the “man with the inexhaustible palette of sound in his instrument” (Michael Tschida) speaks about changing times, his best moments, and his love for a music that can encompass everything.

Throughout your career you’ve always been open to other cultures and styles; you’ve traveled between genres in a way few others have. Is it your best quality?

Wolfgang Puschnig: It just happened that way. Meeting people, meeting other musicians led to other things. I was never shy, never afraid to try things out, so I never had to retreat to the position of the “cultivated European” who supposedly knows what’s good. That’s why it was easier for people from other cultures to communicate with me, for us to find common ground, while avoiding any hint of exotism – just decorating yourself with the trappings [of the culture]; I always hated that – but naturally, not motivated by some plan or calculation.

World Embrace, a great 4-CD box set that came out on your 66th birthday, is a good introduction to your work.

Wolfgang Puschnig: Yes, that’s not a bad selection. But there were a lot more possibilities as well. The Konzerthaus [Vienna] was kind enough to offer me the chance to do it, and I gave them a list of options, from which they chose.

The range is incredibly broad – from Philadelphia to Korea, then back home to Carinthia.

Wolfgang Puschnig: When you’re in the middle of it, it doesn’t seem that way. It was always normal to me, and I always enjoyed the process more than the result.

Why? Are you so self-critical?

Wolfgang Puschnig: No; I just always loved that time where something is being created, where you work to find common ground with other people. Because it’s not about having a specific goal or aiming at some sort of perfection from the beginning on. I also enjoyed it when things didn’t work immediately; that’s part of the process too.

For someone who has traveled as much as you have, it begs the question: why come back to Austria at all?

Wolfgang Puschnig: Well, I was never completely gone – through the things I did, sure, but home base was almost always Vienna, and my family is in Carinthia.

“It was music willing to integrate anything, as long as the music that came out of it was good.”

But with the time you spent in New York and Philadelphia with your wife, Linda Sharrock, didn’t you feel somewhat at home there? Carla Bley wanted to arrange a Green Card for you in 1988.

Wolfgang Puschnig: Carla thought I should do it; she was going to help me and it would have been no problem. But I decided not to, maybe because I’m a country boy at heart. And because I was never really comfortable with the business model in America, it just felt wrong. If you’re talking about jazz, sooner or later you end up in America, it’s true. Jazz is actually a cultural creation of Black Americans. The crazy thing is that it never comes to light. Steve Swallow said to me once, “Wolfi, the history of this music is not what you read in the books.” One thing that drew me to this music was that it never shut anyone out. In spite of the history. It was music that was willing to integrate anything as long as the music that came out of it was good. Here in Europe, that ended up in the arts branch, to a great extent. And as much as jazz was once popular music in the U.S., it’s not anymore – it’s too bad, but it’s also a natural development.

When you look back, are you a little bitter about the fact that certain works – like Alpine Aspects (1991), which combined deep funk with the brass band sounds of the Amstettner Musikanten – might have been more successful with the help of a substantial marketing campaign? Or are you mainly satisfied with the way things went?

Wolfgang Puschnig: I’m not bitter at all, no. I was never chasing after huge success. I did notice, of course, that Alpine Aspects had a completely different effect when we played it in France or England – much more positive, more euphoric. It wasn’t till ten years later that that improved here; at the beginning there was a lot of resistance to it.

Maybe the time wasn’t ripe for it; maybe you were just too early.

Wolfgang Puschnig: Could be, but you can’t control that. I don’t think about it; for me, it was a great project. I knew the band director in Amstetten from my student days, and with the American colleagues, it was really something special. The great thing was the openness from both sides – from the brass band as well.

You were a founding member of the Vienna Art Orchestra. What was that period like, in the late 1970s?

Wolfgang Puschnig: That was a completely different time, a time of awakening – at least for the younger generation I belonged to. At that time, we in Vienna had no hope of getting in contact with the older “nobility” of the Vienna scene. So we formed a young band and tried to do our own thing. Mathias [Rüegg, VAO bandleader] was a big part of that. It was a great accomplishment on his part, but it came out of a group effort. One person can’t do something like that alone. It was a collective movement. At that time, no one was thinking about getting famous. Of course, it was great if you could earn a little money doing it.

Regarding influences: you’ve played with a lot of stars, but a few of your fellow musicians really became companions, like Jamaaladeen Tacuma and Jon Sass.

Wolfgang Puschnig: Yes, they’re like family. But Harry Pepl and Hans Koller had a big influence on me as well. Koller was a mentor to me. And Carla Bley and Steve Swallow. I’ve known Jamaaladeen for so long now, it goes far beyond the musical connection.

In an interview with Andreas Felber for your 50th birthday, you said: “I’ve realized that the best moments for me are when I, as a person, am not standing in my own way.” That sounded like wisdom beyond your years to me. When and how do moments like that occur?

Wolfgang Puschnig: Unfortunately, there’s no recipe for it, otherwise I’d be a billionaire. In music, you can control a lot of things, but you can’t control how the listener perceives it. In the end, as a musician, you’re a medium. If you can succeed as a medium to communicate something that is somehow enriching or comforting, something that transcends everyday life, that’s great. There’s not a whole lot more that you can do. And then there’s no pressure to want to be “great”.

One album that helps me transcend my everyday life is the live album with Nenad Vasilic at Theater Akzent. It’s a great album, and it’s fortunately available on vinyl as well. How did it come to be?

Wolfgang Puschnig: Nenad had asked me years earlier if I’d be interested in doing something with him; he gave me a CD that he had made, and I really liked it. So, I said yes – but as it happens so often, it kind of got forgotten because we both had a lot of other things to do. And then he asked me again if I’d play at Theater Akzent, and we rehearsed and played the concert together. Nenad is a fine musician and a great bassist. The music he writes is really good, too, and we have same perspective about music. Like me, his starting point is the material he comes from. He’s a Balkan expert.

“That so-called ‘blues feeling’ exists in many musics, in a different form.”

What is that material for you? Carinthian folk songs?

Wolfgang Puschnig: Yes – interestingly, I didn’t realize till much later that there’s a melancholic, sentimental strain buried in that music. Every now and then an American colleague would say, “You sound like the blues, but in a different way.” And I figured that has something to do with it. That so-called ‘blues feeling’ exists in many musics, just in a different form. When we say ‘blues’, we mean blues from the United States, yes – but I’ve heard blues just as strongly in Korean music; I could feel it there, too.

Like Balkan music and Carinthian folk songs?

Wolfgang Puschnig: Yes. A kind of basic emotional vibration that turns up in a lot of cultures.

Your son is studying piano at the music university in Vienna. The title of a new biography by a musician has the great title How Music Saved Me from Success. Why didn’t you to keep your son away from music and putting him on the track to success?

Wolfgang Puschnig: (laughs) I had no influence on him; I didn’t try to either deter him or push him into it. He decided that himself. I told him, “If you really want to play music, I can’t encourage you, but I also can’t say anything against it.” It’s not the easiest way to make a living in this society. But inside, it’s another thing entirely.

The Klagenfurter DonnerSzenen [cultural festival in the Carinthian capital] asked your son if he wanted to play, and he said: “Yes, I’d like that, together with my father.” Seems like you must have done something right as a father…

Wolfgang Puschnig: I never thought about that before, to be honest. He called me up and said he had the chance for us to do something together at the DonnerSzenen, and would I like to do that? Would I, indeed…we’ve already played twice in Porgy, the last time at the Klassiktreffpunkt. That time it was reversed – Christoph Huber, who’s known my son since he was little, asked me if I’d like to play with him. I honestly wouldn’t have dared to ask him myself; he’s a little hesitant about that kind of thing.

Why? Is it the son trying to step out of his father’s shadow?

Wolfgang Puschnig: Of course – you distance yourself during adolescence and later as well, and over time he realized that I’ve played a relatively active role in the jazz scene, but we’ve always had a good relationship in general. When he asked me to play, I was really happy – it showed me that he’s become more relaxed. He has very high ethical standards for himself, you see; he doesn’t want to [take advantage of me being his father].

You’ve played with a lot of pianists. What’s special about playing with your own son?

Wolfgang Puschnig: I never compared. What we did together, and what I felt, felt completely natural to me. Sounding together. I felt great. Maybe it’s the genes.

He said he was very nervous playing with you.

Wolfgang Puschnig: He was stressed because he thought he had to do something extraordinary, something particularly good. And I keep telling him, that’s not what it’s about. The only people who will ever hear how precisely you play a run, or how clever your harmonic movement is, are the die-hard jazz specialists. That’s not what’s important. Playing music with the intention of showing how great I am was never my thing.

That’s audible in your playing.

Wolfgang Puschnig: If it is, I’m glad to hear it.

Until recently, you taught at the university yourself. Do young musicians have it easier or harder than twenty or thirty years ago?

Wolfgang Puschnig: Both. Their technical ability on their instruments is much better than when I was studying, because they reach a high level much earlier – just in terms of technique and the whole learning process. But they’re confronted with a flood of information, which makes it harder to get through that labyrinth, to stay true to themselves and find their own voice.

Thanks for the conversation.

Markus Deiselberger, translated from the German original by Philip Yaeger.