To experience a production by the n ï m company is to watch artists step out of their comfort zones: jazz musicians dance; dancers create and perform music. It’s a melting of disciplines, a dissolving of boundaries, and the audience is cut loose from its normal points of orientation in the very best sense. Naïma Mazic, the mastermind behind n ï m, grew up steeped in jazz and trained as a dancer; in the second part of this two-part interview, she talks about her research into the women behind famous jazz standards, getting into directing videos, and getting booed at a jazz festival. (Looking for part I? You can read it here.)

You’re currently conducting research on femininity in jazz music. How did you come to this?

Naïma Mazic: Growing up in Vienna in a jazz club and in the hip-hop scene, I felt like: where are the women? I just didn’t have role models. It was clear that I could/should play piano and sing, but that’s it. You know, my father always said, “If you had [been drawn] to another instrument, it would have come.” But I have to say that role models are extremely important! If I had seen more female musicians playing other instruments, I think that would have changed a lot for me.

I remember the first concert – 2017 or 18, I think – when I saw a female jazz trio on stage at Porgy. I’m not saying it was the first one of only women, but for me it was. I saw Savannah Harris, Linda Oh and Maria Kim Grand on stage, three of the absolute top jazz musicians for me. And I just cried because I couldn’t believe what I was seeing: an energy I haven’t felt before, a different sound, an unfamiliar way of being with the audience. It really blew my mind.

“There are endless stories, and I wonder how much more we don’t know.”

What has your research turned up so far? What are you doing with your findings?

Naïma Mazic: I wanted to see how I could turn jazz standards into a choreographic score, how I can be in conversation with a song, even on a recording, and become like another instrument – not just dance to the music. Then I realized that all of the tunes I was working with are named after women. I was working with John Coltrane’s “Naima”, Sam Rivers’ “Beatrice”, “Lonely Woman” from Ornette Coleman…and I wondered, wait, who are all these women?

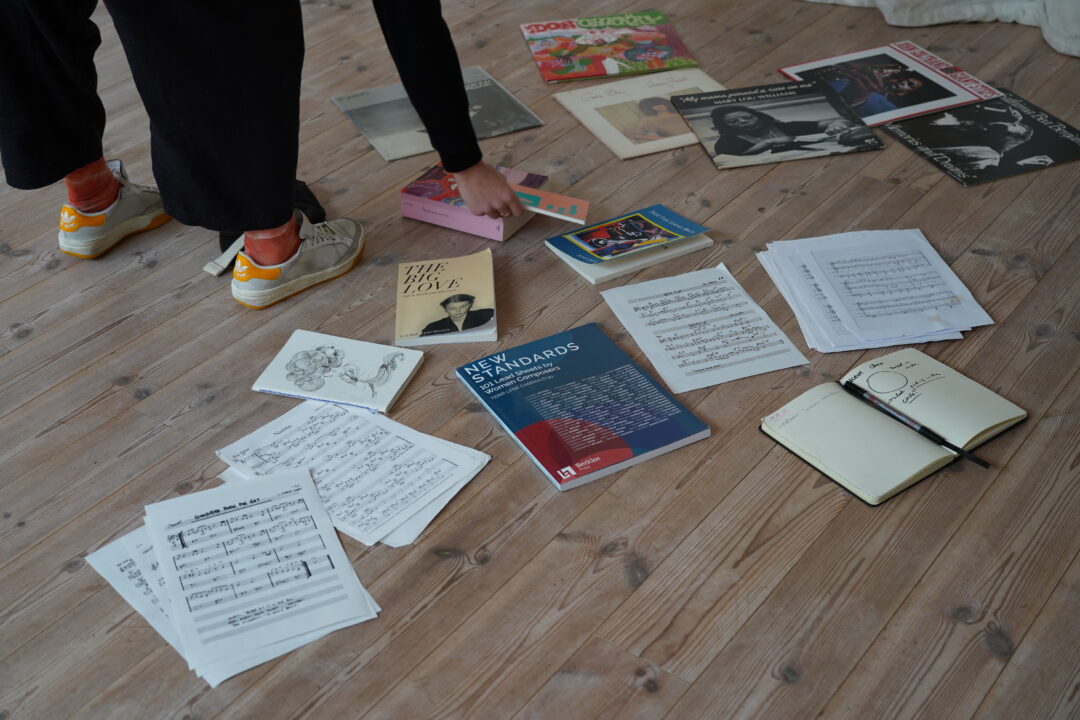

So I started to collect jazz tunes named after women, and in the process I discovered incredible musicians, artists, women. It’s mind-blowing how much material there is, and that’s the basis of my current work, “ALBUM” – the figure of the muse in jazz.

There are the ‘classic’ stories about the women who supported male musicians – managers or artists who gave up their own art, the whole ‘there’s a woman behind every man’ story. There are the female artists who never got as recognized as their male partners, obviously. And the stories of women who gave up their own lives to support their men, especially in the 70’s, when there was a lot of drug abuse, and women became like nurses or hospice workers for their husbands, doing everything behind the scenes.

There are endless stories, and I wonder how much more we don’t know. How many books have been published under a man’s name; how many men have taken credit for a woman’s work? I’m curious about the hidden femininity in jazz. I think there is a lot a lot to discover – like now that Terri Lyne Carrington published the book 101 Compositions by Female Composers: there is so much music that is already there; it’s just often under the rug.

And how is this reflected in your choreography and performance work?

Naïma Mazic: I’ve been working with Golnar Shahyar and with Evi Filippou here in Berlin, and I am in exchange with Maria Kim Grand. At the moment there are three categories I’m looking into: first, songs named after women who have supported [male] musicians or carried on their legacy, like Nellie Monk, Sue Mingus and many more. Second, songs in collaboration with women who were artists themselves, like Moki Cherry, who had the Organic Music Society with Don Cherry, or Alice and John Coltrane, or Lil Hardin Armstrong. Third, songs written by women that stand on their own: Carla Bley, Toshiko Akiyoshi, Mary Lou Williams, Jutta Hipp, the list goes on…

With this project, it’s important to be in service of the women’s voices, but also to think about what I want to tell and leave room for: it’s a performance, not an academic paper. So what we’ve been working on choreographically is taking the stories of the women but also drawing from the music itself, as well as from the figure of the Muse in Greek mythology.

You’ve also recently started directing music videos. Who have you been working with? What have you experienced so far?

Naïma Mazic: I’ve made two music videos: one for Lia Pale and one for TOYTOY, a band from Hamburg. The next one will be for Golnar Shahyar. I think musicians ask me because they know of my in-depth work between music and dance. And in general, I think there is a big interest right now in movement and dance – how music can be embodied, or shown visually through the body. It’s been interesting to work with film, where, for example, there’s the possibility of the close-up, which you don’t have in theater or performance. I can choose that at a certain moment, the rhythm will only be shown by the eyes, or by the hand. I’m fascinated by fragmentation, choosing where to put the gaze, which is interesting, because in music, too, when you do a recording with multiple instruments, you can choose to put the focus on one of them.

I love to work with pre-composed music and think of imagery. I love making a world out of a song through film, finding the connection between dance and music in a way that functions in film. I like blurring the boundaries between short film, art film, dance film and music video. I’ve started working closely with filmmaker and artist Alaa Alkurdi; we will release something we’ve been working on soon.

Over the past 10 years you’ve developed, as you put it, “a method of learning and embodying time and pulse: independent rhythmic skills and polyrhythms to be used as communication tools with musical partners”. What does this look and feel like in practice?

Naïma Mazic: Milford Graves said, “we are not interested in being metronomic.” You can’t cross a highway in a marching step! (laughs) But I practice with my dancers using a metronome. I think there is something about being able to keep time; the body remembers each tempo astonishingly well. So for dancers to actually be independent rhythmically, they have to have certain tools first. There is a basic necessity to keep time, to feel the pulse underneath rhythms; what connects us in the end is the pulse. And for dancers and musicians to feel that and keep time together takes a lot of practice.

But going further, I’m interested in what happens if we dance in, for example, [5/4 time]. Like, there’s the comfortable, known 1-2-3-4… but then there’s this other beat on top. What do we do with it? I’m always so fascinated by what a different meter and tempo do to the body, and to improvisation in dance, because you have to leave your automatism. It takes a lot of practice rhythmically, and then to move on to beats and offbeats, different subdivisions, polyrhythms within the body…I always struggle with, or I’m encountering, the intuitive part – dancing a rhythm by feeling it in your body – as opposed to the analytical approach, counting and being more in your head and less in your body. So the learning phase is super restrictive, but once you deepen your practice, you find the freedom in it.

“if there are many female musicians and dancers on stage, who shows up?”

Can you tell us about your project “PoLy-Mirrors”?

Naïma Mazic: It was the first piece I’ve ever shown at a jazz festival – the Leipziger Jazztage at the Schauspielhaus Leipzig with Georg Vogel and Evi Filippou. We also gave a workshop with a performance the same day for jazz students at the university there and dancers from Leipzig. I’m also mentioning it because the benefit was so palpable. The musicians afterwards were, like, “now I really want to work with dancers.” So I think it’s really something to think about regarding education; it’s time to start implementing this. And I was so happy and inspired by the situation; we were really surprised that the younger generation was so into it.

What was also interesting was that I got my first “boo” there after the PoLy-Mirrors show.

Really? And you found it interesting, not offensive?

Naïma Mazic: Yeah (laughs). I had to think of my dad showing me “Boo to You Too” by Carla Bley. Afterwards I was told that it was one of these “jazz police” types – you know, there are a lot of these older white European men at jazz festivals. So I’m also really interested in the fact that this work I’m doing brings new audience members. Who comes to see jazz and dance – and if there are many female musicians and dancers on stage, who shows up?

So I actually took it as a compliment: if we get booed at a jazz festival, where I know it’s not related to the quality but that it does something to somebody that strongly, then it’s very interesting. It shows something about this scene – how open musicians are to working with dancers is one thing, but how open is the audience? How open are the clubs? How open is the world?

In “PoLy-Mirrors”, I’m interested in how diagonals in and through the body perform something that is perceived as feminine – the gaze, the eyes, the tilting of the head, the twisting of the body, [like with] Virgin Mary figures. Also in European Baroque and Renaissance paintings, it has clearly been made into something feminine. It was very interesting to use this choreographic conceptual tool while working with a composer, finding out that the diagonals are maybe creating something we perceive as submissive – but also something powerful: in the body, you need diagonals to create groove. The composer, Elias Stemeseder, and I approached this from many angles. It was a beautiful way of working – closely together, but also independently.

It’s a great example of how organically these two fields can work together when you are open to it.

Naïma Mazic: Yes – and I have to say, one piece that Elias wrote using choreographic tools [and] that we talked about is played a lot now. I’ll come to a club in Berlin and hear it; Evi has it on her new album as well. I’m very thankful that she put it in her album notes that it was created for “PoLy-Mirrors”, with the n ï m company. I think we have a responsibility to credit each other. If word would be spread more that a piece has been done in collaboration with a choreographer and dancers, maybe more curiosity would arise for other people to work with dance. It shows that the work keeps going on.

You’re bringing (at least) two disciplines together. Could you imagine a term for this? Like, let’s say you were to offer a class at a university, or even an entire curriculum?

Naïma Mazic: Hm…maybe ‘the musical body’.But I need to think about it.

What have you got coming up?

Naïma Mazic: A few things, actually. An initial, shortened version of “ALBUM” will be presented at the LAKE Studios 10th Anniversary Festival in Berlin on the 23rd of June, and the actual premiere is from the 12th-15th of October at Brut (Vienna).

I’m also performing on the 16th of June with musician Maria Coma at the SOUNDANCE Festival in Berlin at DOCK11. And I just got invited to show my work at the Bozcaada Jazz Festival in Turkey in September.

Looking forward! Thanks for talking with me.

Arianna Alfreds

“Hear & Now – Danced Jazz Tunes” session for musicians and dancers on May 7th, 6-9pm in the Strenge Kammer at Porgy & Bess (to participate, email more2rhythm@gmail.com)