PETER ABLINGER does not think about expanding the concept of music, he reflects on and reacts to music history, creating a theory of perception of sound. At the end of last year he received the AUSTRIAN ART PRIZE FOR MUSIC for his oeuvre. Recently, a record with important orchestral works of the past decade was released by GODrec. In conversation with Sylvia Wendrock, PETER ABLINGER looks at the question of what a Mondrian in music might mean, at reality, and at the helpful trait of oblivion.

Your homepage seems like a treasure trove, an archive; one gets an incredible insight into the wealth of your work and reflections.

Peter Ablinger: The website has also become the first place I go to when I’m looking for something. I put the relevant information online for each inquiry, and so an order has developed over the years, an orientation that is as clear as possible. First and foremost, it should be practical and accessible, easy to use.

How did you develop your self-understanding of presenting your works, of bringing them into an overview?

Peter Ablinger: A good part of it is simply natural disposition, a certain sense of order is part of me. It has a certain recreational value for me to arrange books on the bookshelf and the like. When the internet opened up the possibility of creating a website, I found that incredibly relieving, because even in the early 1990s, sending my works by mail took up half a day’s time almost every day.

How do you concentrate?

Peter Ablinger: I don’t have a problem there. Stressful periods are rather the travel periods with many movements and appointments. In times with few appointments, now with corona in particular, my daily routine is more like that of a monk. I ride my bicycle to my studio in the morning, then I’m there all day, return for dinner together, and after that I usually take care of emails. In the studio, I deliberately don’t have internet, I don’t use the phone and can not be reached in any other way. So there, it’s only concentration and me.

“[…] I FORGET SO QUICKLY. A VERY HELPFUL TRAIT BY THE WAY”

Speaking of corona, how did you come up with the “Corona Suite”?

Peter Ablinger: The piece came out of a hole I fell into when corona started. But although it feels like corona is to blame, it’s not the case: a big commission that was just about to start in March, for which I had made space to work on, exclusively, over the next three months, fell through. I can’t even remember what it was, because I forget so quickly. A very helpful trait, by the way. So suddenly there was nothing to do and at the same time the lockdown came. I also had an intense phase of reading Samuel Beckett again – while his plays often have something clownish about them, his novels often seem very autobiographical to me. So, along with Beckett and the corona atmosphere, I was drifting towards depression, feeling a sense of futility, and feeling that the other countermeasure, i.e. to start writing a piece, was also futile. So then I did the most pointless thing as such, some nonsense that I never thought I’d ever do: writing little nonsense ideas into my notebook, a kind of little daily tasks. Then, together with the corona blog, I was able to slowly bring that all together.

So it’s a clown suite, a kind of notepad, but not an examination of corona …

Peter Ablinger: Not directly, of course, but even if the motifs are composite and not only the fault of corona, it is still an issue. In the blog, for example, I addressed the futility and described how nonsense is possibly the only thing that can support you or, in a certain sense, justify art, and then I acted accordingly.

Is my impression correct that visualizations have steadily increased in your work?

Peter Ablinger: It’s true that I’m releasing more of them or also producing videos, for example, because access to production has become much easier. But the importance of visuals has of course always remained the same for me. As a teenager I didn’t know, am I going to be a visual artist or am I going to be a musician? For me, both were essential and equally important, and in a way remained so, because visual art always was and is my companion and inspiration. Which brought about essential developments: phonorealism is, of course, an attempted analogy to photorealism. When I was nineteen (I was still a jazz musician then) and stood in front of a huge photorealistic painting for the first time, my most impressive questions were: what the heck is this and what would it mean in music? Since then, this question never left me until I finally came across the digital technologies in the experimental studio in Freiburg in the 90s. I had questions about technology that went beyond the previous instrumental solutions, had to find new approaches, and got answers in Freiburg. I was then able to continue working with Peter Böhm in Vienna and finally perfect the work over decades with the IEM Graz.

Your search is about the translation into music – from this, concepts arise which necessitate technical progress to be realized, which in part still took decades … so now things have been realized which you already had thought about long time ago.

Peter Ablinger: In the case of phonorealism, it’s clearly like that. I knew about the incredibility of my thought about possible “phonorealism” as a nineteen-year-old. I was totally excited because I realized that the question on its own was insanely important, even if I didn’t have any answers. The first step was as clear as it was simple: if painters start with a photograph, I had to start with a phonograph, that is, a recording. Immediately afterwards I made my first field recordings. As a jazz musician at the time, I first began to improvise upon these, since I didn’t have anything else at my disposal. A kind of amalgam, to merge the recording with the instrumental sounds in such a way that it all becomes one thing, was what I had in mind. My improvisations did not satisfy me. But the direction was taken and never forgotten. It was only when I came into contact with digital technology in 1995 that I suddenly realized how it could be methodically implemented.

Which indicator is telling you that you’ve come up with such a great idea?

Peter Ablinger: Perhaps this inner excitement that I’ve described, but often also more a kind of fright, a fear: Really? Do I really have to do this? And even though sometimes I find it almost to be an imposition, it’s clear that I need to do this. Sounds like a terrible artist cliché. I decided to become an artist when I read the admittedly very kitschy biography of van Gogh, at the age of thirteen. But that’s how I am experiencing it.

This decision is an essential moment in a biography, after which it becomes clear how ideas, thoughts, etc. are dealt with.

Peter Ablinger: Absolutely. In Lacanian terms, it would be the Objet A, a nothingness on the horizon that one follows until it becomes true. An illusion in my head that I’m not going to let up on until it turns into reality.

And you then decompose this reality with your works by showing the inconstancy of human perceptions?

Peter Ablinger: The technical term would be the various registers in which the concept of reality is playing. The work that has become real, that is now on my list of works, that is performed or installed, is of course a different register than the thematization of reality IN my work. Because there it’s mostly not about the reality of the piece itself, but about a specific concept of reality, which, if we stay with the example of phonorealism, plays a rather minor role in music history, namely the depiction of reality, quite the opposite to the visual arts, where it kept a central value until the age of abstract art. So bringing a traditional music setting into an encounter with the concept of reality, like street noises, promised to be exciting and to raise completely new questions and contexts. This was only the first step, which would be then methodically expanded in the mid-1990s.

And then came the “electronic years”?

Peter Ablinger: Very soon, questions of perception arose from this. For example, when in the pieces for computer-controlled piano the piano makes an approximation of language, actually only a vague, spectral approximation, because the piano cannot directly reproduce language, but it represents a certain impression of the voice. By some support with subtitles, one even thinks that one is hearing the piano speak. This “recognition” of the voice sound is of course an illusion, as it only works with very familiar texts (without subtitles) or by reading along with the subtitles. There our brain is playing tricks when it is projecting the things being read, thus the acquired knowledge, onto the things being heard; apparently reading goes faster than hearing. Under certain circumstances, one can make out vowels in the piano sound, if one is already on the language path. Otherwise, without text, one just hears a piano gone wild. So there are two completely different realities between acoustic and projected hearing. Actually, the piano gone wild is the real and the supposedly understood language is the imaginary.

The “Quadraturen” sound like a syllabic piano playing – do the sounds of language and instrument contribute to the supposed language recognition or is it rather the rhythm?

Peter Ablinger: That depends on the method. When the computer piano is playing with its very many strokes, it is not exactly the rhythmic sensation, but it has something to do with temporality in an area that is no longer perceptible, i.e. the level of resolution. Closeness to language only comes about with very high information density. The computer piano, after all, plays according to the physical repetition capacity of a key, which is approximately sixteen strokes per second. A pianist could reach this tempo on one key for a short moment with the appropriate finger-double-hand technique, but the computer piano is able to do this on the entire keyboard at the same time and each of these strokes can have a different dynamic. Such a density of information then equals that of spoken language: it is incredible what a quarter of a second of spoken word contains in terms of phonetic material. In this respect, there is a temporal component that gives the impression that the language is for real.

“WHAT COULD A MONDRIAN MEAN IN MUSIC?”

Did you come across that by chance? What roles do language and speech play in your cosmos?

Peter Ablinger: This question leads very far, of course. As a jazz musician I went through the question very excessively. Especially before my free-jazz Cecil Taylor cloud, there were still very much language-oriented piano lines; I wanted to speak with my instrument. When I then began to occupy myself with composition – my first unofficial teacher was Gösta Neuwirth, a very critical mind – the problems of language-like in composed music were expounded. I took up this thread and pursued it further and further: I wanted to expel this language orientation from the music. I was very conscious of it, more so than today’s language-like composers on the scene. People like Lachenmann or Sciarrino seem to lack this awareness completely, since their music is very rhetorically structured, and functions in a narrative way. As a consequence, I spent my 1980s trying to free myself from that. But apart from the aleatorics of John Cage and the early work of Boulez, really just the “structures,” there is hardly any music that doesn’t want to speak. I was looking for something abstract, a tableau that I’d divide in the middle, one half I’d colour blue, the other green – a completely different form of organization. Again, early abstract visual art was particularly helpful to me here. Therefore the question: What could a Mondrian mean in music? I was also fascinated in free jazz by the state when the whole ensemble was raging at its absolute maximum, then the room would be filled with sound, for it all to fall into complete silence, like a surface, like a waterfall, simply like everything. The speaking was gone, the music didn’t have to go anywhere anymore, it was already at its peak and just stayed there, at least for a moment. Those were moments of longing for me, those were the ones I loved and saw in free jazz. And you can probably see, emotionally at least, maybe even structurally, a direct connection between such situations of absolute climax in free jazz and my later preoccupation with white noise, because that’s everything, in physical-acoustical terms.

All colours tend towards white at the absolute maximum of their interplay…

Peter Ablinger: In my first instrumental compositions in the early 1990s, one can hear how I’m trying to translate this static raging into notes. “Verkündigung,” for example, is like super quiet free jazz. In “Der Regen, das Glas, das Lachen” the noise is also announcing itself already; it’s exactly the synthesis of the raging of the instrumental-technical maximum and the standstill of the noise, the waterfall, so to speak. With this piece I also knew that I was not getting anywhere with instruments anymore, and began to look around for new methods in the electroacoustic studios.

A search for pure music that doesn’t act rhetorically, but then lets noise encounter language again?

Peter Ablinger: Noise and language occur less frequently in my pieces, but there it’s precisely not about reconstructing the rhetoric, but rather, for example in “Das Wirkliche als Vorgestelltes,” about the fact that language is painted over with noise, then some frequency windows are cut into these over-paintings and only a certain frequency of the voice remains. For example, a window at 100 hertz leads to the disappearance of all the colours of vowels and consonants, leaving a muffled murmur; if I cut the window at 3000 hertz, only the edges of the consonants are audible. So it’s a purely sculptural consideration of language in terms of its various sonic areas. This is different, of course, in “voices and piano”, my most frequently performed piece: speech and language are definitely prominently placed, but nevertheless the music is not organized rhetorically, rather analytically, with respect to the abstract characteristics of language, to its spectral elements. In a second approach, there’s again a great deal of what could be called rhetoric, because I certainly am operating symbolically and treating the material in an iconic sense according to the motif. So, for example, if I’m portraying Billie Holiday, the piano part will become a bit of bebop. In the process, I need to take a lot of decisions about the way in which the language material is analyzed, the speed at which it is sampled, the grid with which it is sampled, which later turns out as the rhythm. Then there’s the question of the number and quality of the sounds. Or is the whole spectrum of interest? For example, I worked on a Polish voice only in the highest two piano octaves, because the Polish language with its consonants is so rich in this spectrum.

“YES, WHAT THE HECK IS REALITY THEN?”

A literal point-of-no-return for you was the realization that a field of rye is rustling differently than, say, a field of wheat, something you hadn’t noticed in the years before. Do you have a memory of what you heard?

Peter Ablinger: For me, this is more about the conditioning of hearing, that we don’t hear certain things at all if we haven’t learned to hear them. Then they are not there at all, they don’t exist, and we need to have conditioned them first. The rustling of grain did not matter for quite a long time because we did not learn to listen to the difference. Conversely, there’s a story from the early days of ethnology in the early 20th century that an explorer played a Beethoven symphony on a shellac record to an African tribe, and the natives heard nothing because this music had no meaning, no orientational value for them. Here our conversation comes full circle to the one at the beginning, where the sound with and without subtitles offers two completely different worlds, and depending on my conditioning I feel more comfortable in one or the other. And now I’m asking myself: Yes, what the heck is reality then?

Together with the understanding that reality can only be experienced through conditioning and is momentarily also limited by it. Mutual conflation and exclusion at the same time … Should the listener learn to hear?

Peter Ablinger: I don’t see myself as a pedagogue, even if the educational aspect was still very predominant (in New Music), i.e. traditional, with artists until right now. I only want to be allowed to show what I find to be exciting, not unlike a little boy.

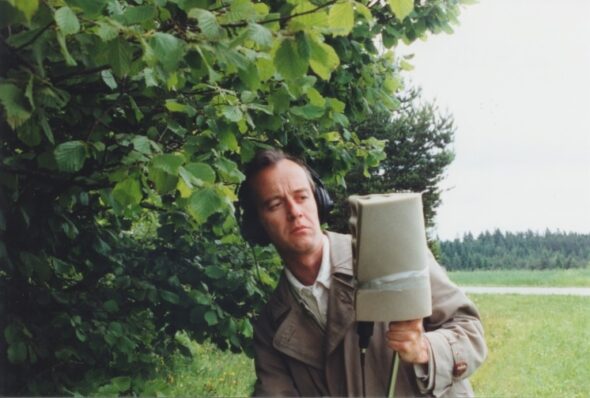

The Arboretum is about field recordings. Was this work driven by an ecological thought?

Peter Ablinger: No, I was concerned about the abstract: a series of recordings of eighteen trees, each tree forty seconds. From the recorded material, I chose the section that was the smoothest, that had only the colour. Many trees I unfortunately experienced only during storms, there is no smooth moment. For example, with an oak or with birch-trees, there’s virtually no movement, they are beautiful, smooth, pure colour. The concept was actually a post-minimalist piece, in which eighteen small squares diverge in their shades of grey. The crucial point is the cut between two trees. The moment that falls out of time, that doesn’t actually exist in reality. Only when I’m changing from one tree to another do I experience the difference in colour. In nature, I would have a cross-fade and no cut, I wouldn’t be able to perceive it that way since one colour is fading into the next one. A cut reveals something completely different to me. With my work I understood what the world is, it is, so to speak, the analogue, the continuous. Recognition makes differences, introduces these cuts somehow, creates a digital level. The application of words to describe this reality is precisely this process, it’s something digital. We are making a cut by telling a thing that it is blue, while it’s actually something much more complex. We are making cuts and are reducing it all to a few levels only because we just have very few words for colours, are are choosing a scale even though the pitches between two semitones are already infinite. Writing is also digital, these are all patterns that we are applying to create a reduced image. In doing so, we are destroying the analogue, self-sufficient metaphysical reality that, of course, does not exist in this (digital) way.

Does the usage of music-theoretical terms such as suite, sarabande, etc., involve references or critiques?

Peter Ablinger: From Gösta Neuwirth I learned to reflect on and react to music history and continued in this direction. Even though I’m often quitting the traditional musical setup or leaving it behind, I’m not thinking about expanding the concept of music. On the contrary, I’m basically interested in the traditional setup only . I just need to criticize it all the time, because I want to save it, and renovate it, in any case. When I seem to be going someplace else, I’m actually just going backwards. With my back to the door, I’ll continue looking at what I love: the concert. And walk backwards out of the hall so that I’ll better understand what such a hall is like. And I’ll continue walking backwards down the concert hall stairs, out of the concert building, walking backwards to the other side of the street, so that I can see what such a concert building is about. What are its neighbouring buildings, which social structures are there? Then I’ll soon come across the Beethoven monument or I’ll be standing somewhere in the garden of the University of Fine Arts.

Thank you very much for the interview!

Sylvia Wendrock

Translated from the German original by Julian Schoenfeld

Links:

Peter Ablinger (Zeitvertrieb Wien-Berlin)