These days, it’s impossible to imagine jazz in Austria without the JazzWerkstatt Wien. In point of fact, however, the artistic collective was founded twenty years ago, in 2004, by Daniel Riegler, Peter Rom, Clemens Salesny, Bernd Satzinger, Wolfgang Schiftner und Clemens Wenger, to counteract the lack of performance opportunities for young musicians. For their 20th anniversary, the JazzWerkstatt has put together a year-long program of events, the next of which – “10 Acts In 10 Minutes” – will take place on March 10th at Porgy & Bess.

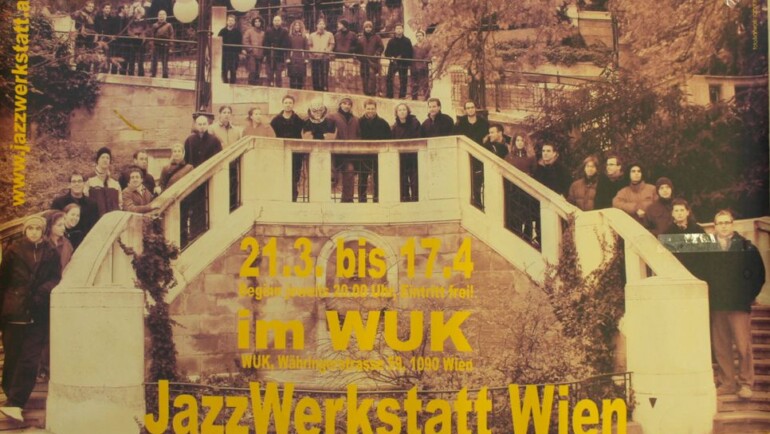

The first JazzWerkstatt festival in 2005 was a wake-up call for the Vienna and Austrian jazz scene: for 27 days, musicians – many of whom had never met before – came together at public rehearsals and concerts. The event, and similarly expansive festivals in 2006 and 2007, spawned a wave of new ensembles, like Studio Dan and Fuzz Noir. Eventually, of course, these utopian happenings – a combination of artistic revolution, networking, and epic party – had to bow to the limits of their founders’ energy and financing. In later years, the festivals grew shorter, but they also grew more focused, as the JazzWerkstatt developed a flair for daring programming and innovative publicity. And through it all, their insatiable artistic curiosity remained. They collaborated with musicians ranging from Die Strottern, to Dorian Concept, Elliott Sharp, members of the Klangforum Wien, and collectives throughout Europe; they pioneered formats such as podcasts, open-source composition, music theater, and multimedia production. Between 2005 and 2023, roughly 600 artists took part in JazzWerkstatt events and productions; the house label, JazzWerkstatt Records, has chalked up 82 releases to date.

However, their greatest service to Austrian jazz isn’t measurable in statistics. The JazzWerkstatt Wien gave the impulse for an active and self-aware jazz scene in Vienna – a meta-collective of sorts – characterized by openness, solidarity, and political engagement. The current leadership includes three of the founders and four members of a musical generation that grew up with the JazzWerkstatt – a clear sign that the collective will continue to serve as a source for new ideas, concepts, and energy for Austrian music. Philip Yaeger recently spoke to Manu Mayr, Clemens Wenger, and Beate Wiesinger about the JazzWerkstatt’s past, present, and future…

“there was great potential”

Clemens, we met at the first JazzWerkstatt festival in 2005, but your story actually begins a year earlier. Was there a specific event that started the whole thing off?

Clemens Wenger: As I remember, the sessions a big part of it. They were the only place where new music by young artists was getting played. We weren’t interested in participating in jam session culture, though. Instead, we started bands – some of which only existed for a single night – and sort of “abused” the sessions as a forum to try out new music. Gradually, more people started showing up who wanted to do something other than play the Great American Songbook or improvise freely. It was a generation searching for other forms of expression – not just artistically, but formally and in terms of infrastructure. We knew there was great potential in the city – so much energy, so many people that were getting to know each other.

Clemens Salesny and I were going to all the sessions at the time, and he had this book – Jazz in Austria 1920 – 1960, by Klaus Schulz – where we found out that Friedrich Gulda had founded [such a collective] once before. They rehearsed in a club on Petersplatz in the afternoon and played concerts in the evening, like Charles Mingus’s Jazz Workshop. And I thought to myself, someone should really do something like that. So, we looked around for people who were artistically active, but who were also ready to get their hands dirty, so to speak. Different kinds of people – bandleaders coming from different places.

Did you know each other already?

Clemens Wenger: We all met for the first time in 2004 in a café in the 9th District. Clemens Salesny invited Daniel Riegler and Wolfgang Schiftner – I barely knew Daniel and I had never seen Wolfi before. I brought Bernd Satzinger and Peter Rom; Peter had just gotten back from America…not an in-group in any sense. We presented our idea and no one ran away, and so we founded the group.

“It’s become more colorful”

And now you’ve been around for twenty years. What’s changed since then? Are there more opportunities to develop and present individual music, individual projects?

Manu Mayr: I was a teenager when the first JazzWerkstatt happened, and it was really important for me – they created an infrastructure that I was able to kind of grow into. I profited hugely from that milieu. It encouraged me to develop my own ideas and offered me a framework in which I could present them.

Beate Wiesinger: It was similar for me – the JazzWerkstatt had always fascinated me; they really did a lot to make promoters notice my generation. But I also think it’s become more open, more colorful.

In what way?

Beate Wiesinger: In every way. I feel like a wider range of musical forms is welcome now. At the beginning it always seemed like they were mostly operating in a small clique.

Clemens Wenger: That’s true.

Manu Mayr: There was always the question, too, of what the JazzWerkstatt actually is and who belongs to it. That was part of the inspiration for our anniversary theme – “All The Things You Are”. I think this legendary aspect was part of what led to a lot of other collectives being founded – which is extremely positive.

“We took networking seriously”

Exactly – there were “spin-off” projects in Graz, Bern, Zurich…for a while, you also collaborated with other collectives. Is that kind of thing still happening?

Clemens Wenger: We still have the most contact with Bern. For a while, there were serious efforts to link the collectives at the European level – with Bern, and also with collectives from Berlin, Brussels, Italy, and France. Networking was a big catchword in the early 2000s, and we took it seriously. Over time, though, we noticed that it was just a marketing strategy for a lot of people; not many of them had an interest in developing actual networks. I noticed that we were mainly providing infrastructure for others, that a lot of people were just using us as a platform for their own bands. Which is understandable, but that’s not why I do that kind of work. Maybe we just didn’t have the capacity to do it effectively – we are involved with our artistic work, after all; everything else is always close to being too much.

It seems to me that there are more resources for that kind of thing now than there were 20 years ago.

Manu Mayr: Yes, but it’s more promoters who seize those opportunities, together with the [music] export offices in different countries. I also think that the collectives in other European countries have somewhat different structures and goals. They work differently, and they have different areas of concentration in their work – all of which doesn’t make networking any easier. There are a lot of export opportunities, it’s true, but my feeling is that national markets are still relatively closed to outsiders.

Manu, when you joined the JazzWerkstatt curating team 10 years ago, did you have concrete ideas that you wanted to realize? Have you been able to do so?

Manu Mayr: I have pretty clear musical ideas and things that interest me. Back then, I was going to at least one concert every evening; I had a good overview of what was going on in Vienna at the time. It was really inspiring to be able to suggest musical projects that I felt should be getting more publicity, or things that would be a good match with the JazzWerkstatt. It was a nice feeling to be able to give a little bit back.

Do you remember what your first suggestion was?

Manu Mayr: I don’t, unfortunately…

Clemens Wenger: Let me think – didn’t you invite Virginie Tarrête, that first time on the Strudlhofstiege?

Manu Mayr: Right, the harpist from Klangforum Wien.

“It has a good energy”

Beate, the same question: did you have concrete ideas that you wanted to realize? In terms of music, programming, or whatever?

Beate Wiesinger: At my first festival [2021’s “A Day In The Life”], it was a new experience for me to get that kind of overview of the music scene…I think I suggested HUUUM. It’s always cool to be part of a group where different interests are represented. I often suggest bands where I have the feeling that they’ve been around for a while and should get a spot – a lot of times it’s not about my personal taste at all.

So, one member of the group suggests something, and you all talk about it?

Beate Wiesinger: It’s a very open process, but everyone definitely has strong opinions of their own. Acts do get strictly declined as well. But I value that, too – it has a good energy.

Speaking of artistic openness: the JazzWerkstatt has always had kind of a penchant for spectacle – I think of KoenigLeopold, for example, or your legendary cooking shows…is there also a conscious effort to present things in an open, innovative manner?

Beate Wiesinger: Yes; I always found that humorous way of presenting things very likable. You can definitely consider that a kind of openness. But also – I don’t want to step on anyone’s toes, but I think that some of the bands that play now maybe wouldn’t have had the chance ten years ago, for stylistic reasons.

“There’s a lot more Solidarity”

Pop bands, or…?

Beate Wiesinger: Among other things. I think there’s a lot more solidarity in the scene now. A music scene doesn’t just consist of musical ideas and like-minded musicians; I think the social structures have really strengthened, in terms of mutual respect, friendship, etc.

It seems that way to me, too: the fact that people now see themselves as part of a larger group or scene is largely due to the JazzWerkstatt.

Clemens Wenger: I think it was the infrastructure, more than anything else, that really knitted us together psychologically. It used to be that people would rent a rehearsal studio for three hours, and people would just tramp in with their instruments and go straight home afterwards. No one hung out. Now younger musicians are renting studios as a group – there is a certain risk to it; you have to have the self-confidence and be sure that it will work – but it 2004, there was nothing like that. Some people had a room where they could play at their parents’ house; the drummers all had their little practice rooms. It was all so…

Beate Wiesinger: Closed off.

Clemens Wenger: Exactly. And close-minded. It’s great that the scene sees itself as a scene now. When

Daniel Riegler started Studio Dan, it was really something unusual, the people he brought together –

people who couldn’t read music and people who…could only read music. [laughter] I’m exaggerating, obviously…but as Beate says, there are a lot more friendships and connections now; the scene is much more diverse. Our understanding of jazz was narrower; it’s gotten a lot broader.

“It often feels like the Wild West”

What do you see as the greatest challenges for the Viennese and Austrian jazz scene at the moment?

Beate Wiesinger: I think there’s still a long way to go before we truly understand ourselves as a scene or a big collective. If there are problems, they need to be heard; the scene has to stick together. I think it needs to go in a direction where we develop something like a lobby, that we become more networked, more structured.

The jazz scene as political bloc?

Beate Wiesinger: Yes…but also that standards are established, in terms of performance fees, for instance.

Manu Mayr: I think you have to find a way to bundle these many small groups and individual interests, find common ground that you can communicate politically. In some form of union, or something like that. It does often feel like it’s kind of the Wild West. The money issue, for example, or our bargaining power in comparison with other players in the branch.

Clemens Wenger: We also have to make sure that the existing infrastructure doesn’t decay, pay attention to what’s happening with the big festivals and clubs. We can’t take them for granted. If the things that anchor our infrastructure disappear, a whole lot could collapse. It’s a house of cards.

The media are part of that as well: Ö1 is actually the only way to reach a national audience for certain kinds of music. We have to fight for every hour that jazz gets played in the afternoon. The scene should be applying pressure here: we’re connected.

“We have to fight for every hour that jazz gets played”

Seeing Ö1 as more of a partner and less of a tool.

Clemens Wenger: Exactly. The educational institutions need to be involved here as well. At every press conference about the “optimization” of the ORF stations and formats, every music professor should be protesting with all of their students. “We educate musicians year after year with tax money, and the public broadcasting network can’t muster the infrastructure to bring this talent to audiences.” Austria is disguised as a “nation of culture”, our conservatories are among the best in the world, and we let these investments just go to waste.

That brings me to my last question: where is the JazzWerkstatt headed? Could you imagine taking over an institution like Porgy & Bess someday?

Manu Mayr: I’m going to immediately say no…but it’s an interesting question, because actually we all ask ourselves why there are no music professionals in the jazz scene.

People doing booking, management, and so on.

Manu Mayr: Right – they all seem to move somewhere else. There are degree programs, but most of the people end up in the big houses, where they program a different kind of music. People like that should take over Porgy, when it’s time. I’d rather think about my artistic content than about booking hotel rooms.

Clemens Wenger: Yes, that’s actually another challenge – making our scene attractive to cultural professionals. It’s extremely important that people like that come to us as well, not just go straight to the Bregenzer Festspiele…

“It’s a great workplace”

…or into the pop business. Isn’t that partially a financial issue as well? Jazz doesn’t really have a reputation as a music you can get rich off of…

Clemens Wenger: I don’t know; I think lot of things work pretty well. I mean, you’re not going to end up in the executive suite, but [Porgy & Bess, for instance] is certainly a great, stimulating workplace. It would be great to have professionals in positions like that instead of untrained artists who start promoting or doing public relations out of necessity.

The JazzWerkstatt is an artists’ collective, in the end. We’ve been around for twenty years because we haven’t become institutionalized. We do have a structure, but it’s become much more flexible over time. We also don’t program as much as we used to; we prefer to allow ourselves more time to work on concepts. We don’t want to become a cultural institution, where as soon as one festival is ended you have to start writing the next grant application. We’re probably not going to be high-powered cultural managers in twenty years. We’re in the wrong…

Beate Wiesinger: …line of work. [laughter]

Translated from the German original by Philip Yaeger.